by Natasha Varner

I am haunted by a small trove of turquoise jewels. They were given to me by my late grandmother Victoria, whom I loved dearly, in the months just before she passed. But it’s not my grandmother whose spirit animates these interwoven arcs of silver and stone. No, this ghost is far more insidious.

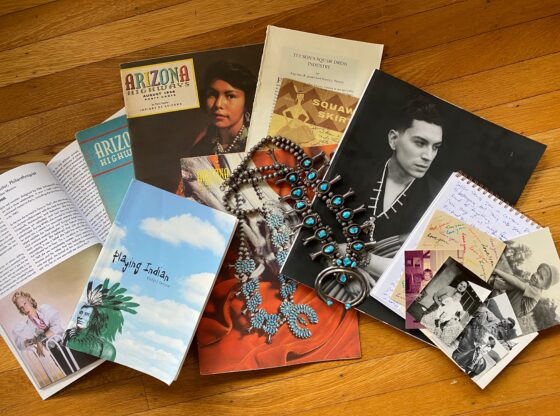

The crown jewel of my small collection is a Navajo squash blossom necklace. A gray shadow of tarnish has dulled its shine but, still, when I hold it I remember my grandmother as her hands, gnarled and twisted by arthritis, fixed the necklace against her chest just so. But when I search the piece for an artist’s initials or try to recall stories about how or when it came into her possession, neither the necklace nor my own memory provide any purchase.

But it’s not the creator of this small relic that haunts me either. The animus is not, in fact, any single being. It’s centuries of occupation, of forced removals, of erasure, of taking. It’s the story of how my family came to thrive in a land that belongs to someone else. It’s my own settler legacy.

Settler memory works in much the same way that the story of this necklace does. Many of us can’t recall how or why we came into possession of the lands we now inhabit; we just know they’re ours. Or at least that’s what we tell ourselves. And we have spent centuries laying down the scaffolding of occupation—freeways, dams, train tracks, urban grids, mines, power plants, prisons, homesteads, resorts, shopping malls. We have made it so that our belonging in this place seems entirely natural. We have convinced ourselves that it is.

In a photograph taken in the early 1950s outside the MZ Bar ranch where my family first set down roots in Arizona, my grandmother sits on the ground with her young sons, my infant father in her lap. She was an elegant woman and here, even beleaguered as she was by dust and early motherhood, she is poised with perfect lipstick, her hair neatly parted and pulled into an elegant chignon. She had only just arrived in Arizona, and reluctantly at that, following her husband who was following a dream of living life on the range.

In the photograph, my grandmother is wearing moccasins and a long, tiered skirt. This simplified version of a mid-century style was known as a “squaw dress,” — the name alone carries a certain sartorial violence in its use of a racial slur — melded elements from Apache, Navajo, and Tohono O’odham dresses and was a hallmark of Arizona’s post-WWII domestic fashion boom.

Credit for popularizing the style is often given to Tucson designer Cele Peterson who once admitted in an oral history, “I didn’t design them. I lifted them. The Indian women were already wearing them….you saw them everywhere.”

Settlers appropriate Indigenous culture and identity not because we want to be Indian but, as Philip J. Deloria puts it in his book Playing Indian, to satisfy our “longing for the utopian experience of being in between.” Adopting faux Indian personas allows us to at once embody the imagined freedom of Indigenous peoples and dwell in the settler imaginary wherein we have total dominion over occupied lands. It helps us achieve a sense of righteous belonging, and it quiets the constant hum of anxiety that reminds us that, in fact, we don’t.

The cover of the August 1954 edition of the Arizona Highways magazine features a squash blossom necklace resting handsomely against folds of red velvet and a gnarled joint of dead juniper. Inside, a sprawling feature explores the history of Navajo silversmithing and trading posts, schooling its readers on how to shop for a quality piece of jewelry. The Navajo themselves are imagined as a sort of quaint anachronism.

“In this wonderfully bright and shining world of ours, in a decade dominated by those men of science who have given us the A and H Bombs, most of us nervous and distraught, plain and ordinary citizens may find some assurance in the knowledge that out in the wide open spaces of this western country of ours simple Navajo craftsmen are patiently hammering out their dreams in silver and turquoise,” writes the magazine’s editor, Raymond Carlson.

Arizona Highways — a monthly magazine whose original purpose was to cover the expanding web of highways in Arizona — had, by the 1950s, evolved into propaganda aimed at getting people to use those highways to access the state’s natural and cultural treasures. Its pages were filled with Ektachrome Indians and meandering articles that romanticized their lives, never mentioning the boarding schools or the economic insecurity of newly established reservations that gave shape to Indigenous existence in Arizona at that time.

I imagine my grandmother seeing this edition of the magazine, which was published not long after she posed for that photo on the ranch, and pining for a necklace she probably couldn’t then afford.

The ranch where my grandparents lived upon their arrival in Arizona sits in the lush desert mountains that roll their way along the western parameter of the city of Tucson. This wasn’t the barren wasteland of cartoon imaginaries – even in the heat of summer the sky swells thick with heavy monsoon clouds, cacti burst with fruit, and the musky smell of creosote makes the air soft and sumptuous.

This is Tohono O’odham land—O’odham Jewed. Land first colonized by Spanish missionaries, called Nueva Vizcaya, then Mexico, then the United States of America. Land that in 1848 was callously divided into separate nationalities by the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. Now the new border wall is scarring its way across that land, leaving the destruction of sacred sites and divided communities in its wake.

I don’t think my grandparents thought of that land as theirs — they didn’t have the deeds or the permanence to have inspired that kind of thinking — but settler memory tends to twist one generation’s manufactured belonging into a certain sense of entitlement.

Today, the land my family once inhabited has changed hands and been transformed into a dude ranch, The White Stallion. And the city of Tucson, where they later established roots, has yawned out over the desert in a seemingly insatiable sprawl. There, settlers continue to weave their narratives of belonging, many now emboldened by family histories that stretch back generations.

Territory, a new magazine published out of Tucson calls itself “the first moderne journal of the Southwest.” The name Territory calls to mind Arizona’s first phase of being a formal entity of the United States – Arizona Territory, a chapter in the long history of settler occupation in that region. The publication is a celebration of that occupation, dressed up in art and design-forward editorial spreads. Claiming the desire to present the Southwest in “a refined light,” the velvety pages of its first issue are filled with carefully crafted photographs of white bodies set against dramatic landscapes of the southwest.

Like me, many members of Territory’s mostly white editorial staff have families who settled in Arizona generations ago. They call themselves “creative natives” who want to pay homage to “our indigenous culture and teachings.” On the magazine’s website they appear adorned in turquoise, set just above the claim that “Territory Magazine holds the keys to the Moderne West.”

Settler colonialism is largely about taking, but it’s also about the stories we tell ourselves so that we can comfortably live with the spoils of that taking. These stories sow a certain sense of belonging, but they also sow a certain forgetting. Those of us with families who have been in a place for a few generations come to see our right to that place as a sort of inheritance. Our belonging to occupied land comes to feel as natural as the continued acts of Indigenous dispossession.

But having deep family history in a place — loving it so much that you have a certain sickness when you’re away too long—that doesn’t give us ownership. No, it only thickens the complexity of our settler relations to that place.

We can’t just cheer as the monuments to Columbus and Oñate and Jackson are toppled around us. We settlers need to learn to see how we enshrine these same relics in our own homes and in the way we think about our presence on occupied lands. We must learn to hold the love we have for place and family alongside unflinching awareness that we, too, are complicit in systems of settler colonialism, and then do what we can to disentangle ourselves from those systems. To repair, and to reparate.

My grandmother died more than a decade ago. At first, wearing her squash blossom necklace felt like an act of love, but now when I put it on I feel a soft strangling. It’s still precious to me in the memories it holds of my grandmother, but it has also come to symbolize this legacy of violence and of taking. Now I see it not an inheritance, but as a haunting. It unsettles me, but that’s exactly what is needed.

AUTHOR BIO

Natasha Varner is a historian and writer with bylines at Public Radio International, Jacobin, Yes! Magazine, and Crosscut. Her new book, La Raza Cosmética: Beauty, Identity, and Settler Colonialism in Postrevolutionary Mexico (University of Arizona Press, 2020), addresses questions of nation building and Indigenous representation, erasure, and resistance in Mexican popular culture. In her work as Densho’s Communications and Public Engagement Director she organizes community conversations, learning, and actions that connect histories of racism and xenophobia to contemporary injustices. Find her on Twitter at @nsvarner.

The author would like to acknowledge Daryn Wakasa and Melissa Bennett for inspiring her to think about ancestral legacies as a form of haunting during conversations that took place leading up to and at “Haunted Healings: Confronting Intergenerational Trauma through Film and Poetry,” an event produced by Densho and the Seattle Public Library in 2018.