By Ximena Espeche

Editors’ Note: Addendum is where we feature original content related to the latest issue of Radical History Review. Ximena Espeche is the author of “Between Emotion and Calculation: Press Coverage of Operation Truth (1959),” which appears in issue 136, Revolutionary Positions: Gender and Sexuality in Cuba and Beyond.

In a recent article in the New York Times, journalist Jorge Ramos of Univision argued that recent developments in Bolivia, Chile, Ecuador, Haiti, Nicaragua, and Venezuela showed that “There is rage brewing in Latin America.” Within that unleashed fury he found some new variables – such as growing inequality and the evolving relationship between protests and their media coverage. He also found a constant: The attraction of authoritarianism, from which Latin America has never recovered. Though Ramos is a critic of the Trump administration’s migration policies and its growing authoritarianism, his analysis of contemporary Latin America as a site of uncontrolled “rage” echoed some of Trump’s own essentializing rhetoric. It revealed a stale diagnostic based on a sort of transhistorical essence, a normative ontology: a democratic state that is “not sufficient” for Latin Americans. Yet if not sufficient for one group, by implication it must be sufficient for another. Here we find the motif that has been repeated over and over in global academic and journalistic analyses of Latin America’s popular mobilization, institutional rupture, and socio-economic crises. We find something similar when the object of study is “populism,” as Ernesto Semán recently argued in the Financial Times.

Casting authoritarianism as a Latin American “tendency” puts a new face on an old explanatory trope, which has been expertly analyzed by Elías Palti.[1] That is, the old dichotomy of traditional society versus modern society, which is then transposed onto Anglo versus Latin; reason versus passion or hysteria; democracy versus authoritarianism. This binary of tradition-modernity underlies one of the most persistent and pernicious characterizations of the region’s supposed democratic failures. That is, the argument that Latin America’s democratic failure is inscribed in the characterization of the continent’s population – particularly the “masses” or popular sectors – as fatally dominated by a lack of reason and an excess of passion.

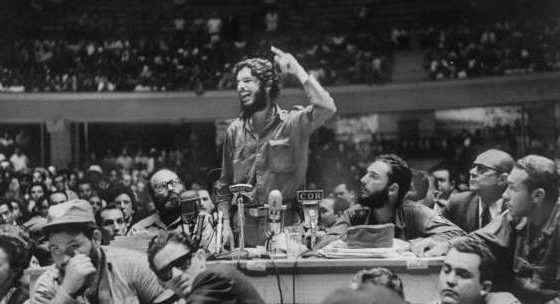

Perhaps one of the most paradoxically rich moments of when this purported division between traditional and modern society came in the immediate aftermath of the Cuban Revolution, when the government on the island launched what it called Operation Truth. Between January 21 and 22 of 1959, the revolutionary government of Cuba invited journalists and politicians from around the world to bear witness to the trials and executions of those accused of human rights violations during the dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista. Operation Truth was part of a battle of information to define the legitimacy of emotion and/or logic as the bedrock of political action in Cuba. The characterization of the revolutionaries as bearers of “true masculinity,” and the positive or negative valorization of being “Latin,” were key themes during Operation Truth. They served to bestow or deny value and acted as a prism through which to observe events, focusing on the capacity to order and channel the emotions unleashed by the revolution and, as well, the revolutionaries’ suitability as calculating men of government.

In order to generate positive media coverage of the revolution, especially during Operation Truth, Cuban leaders took advantage of the uncertainty generated by the revolution, which at the time was still considered by many political analysts and diplomats as an event that furthered democracy in Latin America. They sought to develop a politics of seduction for global public opinion. “Revolutionary justice” was perhaps the biggest challenge for this seduction’s success.

As others have noted, there was a kind of “love affair” between Cuba and the global media. Representatives of the revolution sought and won press support. This had begun before 1959 as a strategy for countering dictatorial censorship within Cuba; after the triumph, it became a way of expanding the revolutionary message. Within this “romance,” the focus on the bearded rebels (barbudos) fueled a characterization of “true manhood.” Castro and his barbudos were attractive because they were rebels with a cause, unlike the models of frivolous or unruly youths so critically portrayed in contemporary film and media. Another quality assigned to the revolutionaries was being “Latin.” Christine Skwiot has shown the way “Latins” could be identified as “white enough” in the sense of “Pan-American whiteness.”[2] According to Van Gosse, ambiguity about the rebels’ racial status was related to the admiration of heroes who were “not exactly” white.[3] Thus “Latin” or “Latino” constituted an analytical problem because it implied an unrestrained – and therefore problematic – emotionality.

The commentaries on the revolution and the Cuban population produced by the media correspondents, diplomats, and politicians invited to participate as witnesses during Operation Truth can be distilled into two groups.

The first group assumed the suitability of the revolutionaries as leaders and accepted the claims they made during Operation Truth. They saw Fidel Castro as a leader who could channel the pent-up demands of the entire Cuban people. Although the legality of the trials was sometimes questioned, for these analysts this did not interfere with the legitimacy of the accusations behind them. They valorized the emotional charge of the revolution as something positive. “Emotion” in this case supposed a pre-rational state, linked to the body. To enter this state implied that feelings would be altered, that actions would be ruled by passion. In this evaluation, that emotionality was appropriately channeled and controlled by a legitimate leadership who knew how to interpret popular feeling.

The second group was made up of those for whom skepticism and/or suspicion eclipsed all else. In general, this perspective – increasingly adopted by publications in the Luce media empire like Time and Life – the trials were considered a sign of what the revolution had unleashed and its leaders either could not or did not want to control. In this case, what was conceptualized as a threat was linked to the “Latin” or “Hispanic” or “irrational” condition of the revolution.

As I have argued in my recent article “Between Emotion and Calculation: Press Coverage of Operation Truth (1959),” in general those who criticized the revolution shared this characterization of it as a wave of emotions that could not be controlled. At the same time, Castro and Operation Truth were discredited for being calculating and publicly manipulating, respectively. The identification of Cuban “hysteria” with the epitome of “Latin-ness” highlighted the leaders’ capacity for manipulation, while also feminizing the leadership. The mention of “hysteria” repeats a long link that threads through many political analyses that have referred to a kind of collective pathology ruled by irrationality and violence, and uses it to explain disorder, either biological or psychological, and is often gendered feminine. References to the revolution’s “Latin” character functioned in this case as a criticism: the move from “Cuban” to “Latin” eroded the new order’s legitimacy.

For those who supported the revolution – albeit critically – the “Latin” condition could be seen almost as a virtue, because it focused on what could be considered a common history among the countries of Latin America. Even when this value was inverted, there was no question of the shared basis of these dichotomies of modernity-tradition, Anglo-Latino, calculation-emotion. The analysts who supported the revolution also failed to question the character of the leaders as necessary guides for the masses, considered potentially dangerous.

These references to “Latin” in cultural and racial terms, seen as inferior relative to the “Anglo-Saxon” world, have been common in US academic and political discourse, as well as in diplomatic correspondence. It reflected a chronic doubt over whether Latin Americans could have democracies like the US – stable governments, trustworthy economies. In Latin American journalistic and political essays of the 19th and 20th centuries we also find these racial prejudices expressed, especially regarding indigenous populations, Afro-descendent populations, or others not considered white. From different disciplines, and different political positions, for both Latin American and US publics, “Latin” could be considered either a value or a weakness.

In this sense, my work, published in the recent issue of Radical History Reviewseeks to make more complex the way in which analyses of Latin America, the Caribbean, “Latinos” and especially “Cuba” have been considered relative to analytical frames derived from other histories, like that of the US. The often implicit comparison with the qualities of US democracy and its leaders likewise repeats the supposedly evolutionary links between traditional and modern society. For example, the assumption that US democracy was representative of “true” and “modern” democratic qualities has been critically analyzed by scholars such as John Fousek and Nils Gilman. These prisms reactive old ideas about the psychology of the masses, such as those advanced by the French scholar Gustav le Bon.

This type of analogy or metaphor, even when used to understand the reasons some struggle to broaden society’s democratic bases, identifies popular politics under the leitmotif of a multitude unleashing its passions, or victim of immoral leaders’ calculations. The use of categories such as a “tendency” for this analysis is useless: it does not help explain social or political processes. Even more dangerous, its explanations are rooted in conditions analyzed as if they were beyond reason. Or, even worse, it defines the actions of a great part of the population through a tautological reasoning, such as that described by Alan Knight in his criticism of the concept of “political culture”: they act that way simply because they have a tendency to do so.

AUTHOR BIO

Ximena Espeche is a researcher at the Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET). She teaches at the Universidad de Buenos Aires. Her book La paradoja uruguaya: Intelectuales, latinoamerianismo y nación a mediados de siglo XX was published in 2016.

[1] Palti, Elías. “La historia intelectual latinoamericana y el mal de nuestro tiempo.” Anuario IEHS, no. 18 (2003): 238-39.

[2] Christine Skwiot, The Purposes of Paradise: US Tourism and Empire in Cuba and Hawai’I (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012).

[3] Van Gosse, “We Are Highly Adventurous”: Fidel Castro and the Romance of the White Guerrilla, 1957-1958” in Christian G. Appy, Cold War Constructions: The Political Culture of United States Imperialism, 1945-1966 (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2000), pp. 238-56

Operación Verdad. Source: Radio Rebelde.

Operación Verdad. Source: Radio Rebelde.