By Rebekah Aycock

In Lethal State: A History of the Death Penalty in North Carolina, Seth Kotch tells the history of the death penalty in North Carolina from legal hangings and lynch mobs to the state’s modern criminal justice system. Kotch offers a brutal account of a modernizing state that relied on and reimagined Jim Crow terror. He explains how the decline of the lynch mob in North Carolina represented not racism’s decline but rather its institutionalization. Lynching was addressed by whites in power as an issue not of racism but of professionalization. For example, the state wanted to not only control executions but control the potential audiences. Kotch’s attention to the role of Black women’s civic engagement is particularly compelling in this regard. After emancipation, legal public hangings drew interracial crowds that concerned white supremacist leaders who felt especially threatened by the presence of Black women. He explains: “By asserting their personhood and that of black men, working class women of color asserted their protective roles… after the Civil War, black women at public hangings claimed civic space and in doing so upset white supremacists.” The shift to private, indoor executions with white audiences was an effort to avoid interracial crowds and to perpetuate derogatory, rather than martyred, images of executed Black men.

Kotch’s careful but unflinching attention to inherently dramatic and violent stories details how the state came out of Reconstruction and into modernity because of, not in spite of, a justice system committed to the execution of Black men. His exhaustive attention to individual cases of capital punishment is just one aspect of his research. His careful consideration of the history of the methods and environments of killing illustrates how decision makers made choices directly connected to the whims of individual politicians and law enforcement officers with little attention to scientific research or social impact. For instance, after a state representative put forth a bill to change the method of execution in North Carolina from electrocution to gas asphyxiation, the legislature passed the bill with the unsubstantiated expectation that gas chambers would provide faster and more “dignified” killings. In 1936 Allen Foster, a Black teenager, became the first person to be executed by gas asphyxiation in North Carolina. Though Foster’s gruesome death horrified the audience, Kotch explains that the legislature refused to backtrack on its decision. Not only had constructing the gas chamber been expensive, but they did not want “to impugn their own judgment, or embarrass their popular colleague.”

Lethal State brings us into the recent past where the death penalty is minimally exercised yet persists as a token of right-wing political alignment. Kotch explains how the decline of executions was a result of the rise of life imprisonment as a viable conviction and not a reaction to the death penalty’s persistent failures. Activist and academic work has been largely unsuccessful in combatting the death penalty as those in power shun research-based arguments in order to keep capital punishment in place. It is Kotch’s attention to public sentiment throughout this history that allows him to make sense of a state’s, and now a political party’s, commitment to a failed system, exposing a trend in leadership’s “overt attention to the emotional satisfaction of the white majority rather than the needs of the wider community.” Kotch concludes by condemning the death penalty as a failure. It does nothing to mitigate crime and represents the systemic, consistent failure to the people it exists to terrorize.

Aycock: Tell us about yourself.

Kotch: I am a home cook, a reliable three-point shooter, and a father. I teach in the Department of American Studies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Aycock: You acknowledge your early coursework as a source of inspiration for this project. Would you elaborate on that journey?

Kotch: I was born and raised in Chapel Hill, never feeling like a southerner. When I started college at Columbia University, I suddenly felt very southern, and was often reminded of my roots. More than one student expressed surprise that as a North Carolinian, I could read (they were joking but the joke wasn’t very funny). So, I gravitated towards classes about the south, and was particularly inspired by Dr. Barbara Fields’s courses and by Dr. Fields herself. She works on the history of enslavement; the death penalty is one of its legacies.

Aycock: Considering both your teaching in the university and in prisons, how did teaching university students and incarcerated students influence this book?

Kotch: Not much, to be honest. This book grew out of my dissertation, which I wrote years before teaching in prisons. But that prison teaching has influenced me profoundly as a teacher and historian and has committed me to doing more work in this intellectual and social space. When someone is incarcerated, they should not lose their right to an education. (Lyle May, who is currently incarcerated on death row, has written powerfully about this.) By participating in UNC’s prison education program, I can help incarcerated students in the same way I help students on the Carolina campus: by educating them about their history, by helping them strengthen their critical thinking and writing skills, by facilitating discussion about issues of importance to them, and by fostering a classroom community that is, I hope, a respite from the inherent violence of confinement. This is a cliché but I am sure I’ve learned more from them than they have from me, about their life experiences, life in prison, the criminal legal system, policing, the war on drugs, and more. And there is something radical, admittedly in a very modest way, about going into prisons and teaching about the 13th Amendment, or the origins of police as the protectors of the wealthy’s property, including people bought and sold as property. Many of my incarcerated students knew these histories, but my classroom offered a space to unpack and discuss them.

Aycock: Your book includes several detailed appendices documenting executions, lynchings, and possible lynchings in North Carolina. What purpose do they serve? Did you always plan to include them?

Kotch: I did always plan to include them but I did not realize how long they would be. Lynchings (particularly) and the death penalty remain underdocumented, which I find/found strange given the gravitational pull they exert on our attentions. The data also allow people another avenue into the story here. I’ve had some good conversations with people who started there when they read the book—that’s how their minds work. Documenting (historic) lynchings has taken up a decent amount of my time in recent years. I’ve been working in my undergraduate classes, and with the occasional graduate worker, to document lynchings throughout the American south in collaboration with Dr. Elijah Gaddis at Auburn for a project called A Red Record. We’ve got a lot of work done but so far have published data only for North Carolina. We named the project “A Red Record” after Ida B. Wells-Barnett’s pamphlet of the same name. The project includes geo-located lynching sites, newspaper articles, death certificates, census records, and more, including lesson plans tacked to state of North Carolina standards for high schoolers. The project has its flaws, but it’s being used in high school classrooms, by community groups, and in commemoration efforts—so in a way its footprint is much bigger than Lethal State.

Since we began A Red Record it has been outpaced by some other lynching maps that look better and are more complete. But we are plugging away at it and seeking to build partnerships with other colleges and universities and high schools to build out the data and experiment with it. We have yet to secure the kind of funding we need to support a network of colleagues but we are still trying. Students do the bulk of the work, using online databases to seek out granular information about lynching victims and perpetrators, to evaluate the content of newspaper coverage, and to try to locate lynchings in space. I get about an email a week from someone who has used the site to track a local story or to learn more about a family member.

Aycock: When describing the limitations of reliable and available sources for lynchings, you turn to Richard Wright’s “Between the World and Me” to explain memory in trauma and the privilege of forgetting. Later, you reference Mark Twain’s A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court when tracing the history of the electric chair. Can you explain the impulse, in these instances or generally, to turn to literature?

Kotch: I must say that I think these two examples represent just the gentlest impulse. Regarding Twain, I think I included it because two of my dissertation committee members were American Studies scholars (I got my degree in history), and I reckoned they’d appreciate the effort. And I use Wright in my teaching, which is how he landed there. But of course, literature (like art more generally) is hugely useful in exploring how people experienced and made sense of the past. I like to tell my undergraduate students that while the job of a historian is often interpretation, sometimes we can simply listen to what people in the past had to say about themselves. Sometimes, the form that takes is southern politicians in the 1860s explaining that they are going to start a war over slavery. Sometimes, it’s art and literature that reveal the values, the mood, the climate of a time period.

Aycock: You identify the 1898 coup in Wilmington as a key moment in the history of establishing white power in North Carolina after Reconstruction. Why do you describe it as an orgy?

Kotch: Now that you mention it, I think I would avoid such a sexually charged term in the future, but I would say I used it because the word expresses a kind of corporeal excess; mass slaughter is just that. But also, the language of intercourse—social and sexual—was often how lynchings were presented in contemporary coverage and commentary and in subsequent histories.

Aycock: You detail how discomfort with the death penalty arose, in part, over fears of being associated with Nazi Germany. You then describe how, a few decades later, American Nazis, the Klan, and the Rights of White People Party lined up in Raleigh to counter a death penalty abolition march led by Angela Davis. Is there a connection to be made between this history and broader current events regarding ICE terrorism, the detention camps, and the visibility of white supremacist organizations, many which openly align themselves with Nazism?

Kotch: In that political demonstration, we see the seeds of our contemporary politics, which are growing in soil nourished by imagined white grievances. This is a good question and I have not given it thought before along its specific lines, but I might guess that with World War II veterans who actually fought Nazis (including Black veterans) being a real force in the polis and the electorate in the 1960s, 70s, and 80s; and with the presence of Holocaust survivors among us; and with generations of political organization around a rhetoric of democracy and interventionism, it might have been much more difficult to pretend that Hitler had good ideas but bad methods. There is a reason why the reactionary right demonizes colleges—that’s where students learn about the past when it has died in living memory. With memory of our anti-fascism erased or ignored, the right is free to pretend that fascist behavior is permissible and necessary.

Aycock: You describe how decision makers catered to a “public feeling,” a “general sentiment,” and, finally, “the emotional satisfaction of the white majority,” at the cost of African American lives. How does this obligation continue to manifest itself today?

Kotch: The death penalty, still. Police murders of Black people. Cynical clucking about “black on black crime.” Mocking majority-Black places, such as Baltimore. Expelling Black children from school. Sending Black youths to prison. Letting Black mothers and their infants die in childbirth. The list goes on.

Aycock: What is next for this project? For you?

Kotch: I am starting a book called Smashed, a social and legal history of drunk driving. I’d like to finish my (collaborative) Red Record project documenting southern lynchings. I’d like to write a fat book on Jim Crow criminal justice. Right now, I am just trying to keep my head above water as the semester thunders forward.

AUTHOR BIOS

Seth Kotch is associate professor in the Department of American Studies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He conducts research and teaches about modern American history, particularly the history of criminal-legal systems in the American south. He also directs UNC’s Southern Oral History Program.

Rebekah Aycock is a PhD Candidate in the Department of American Studies at the University of Kansas. She studies the intersection of the histories of regulating sex and criminalizing Blackness in the U.S., specifically in representations of burglary.

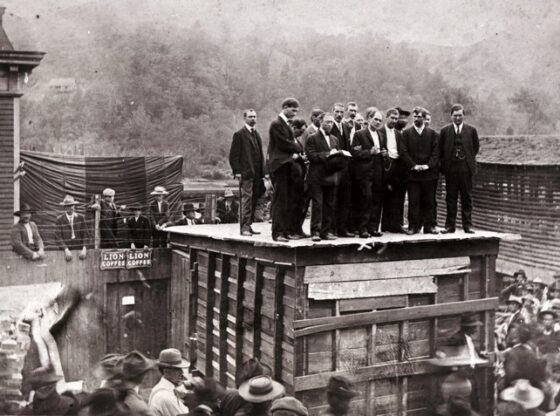

The execution of Peter Smith in Marshall, N.C., 1905.

Smith was allowed to make a public statement before being hanged out of sight of the crowd.

The execution of Peter Smith in Marshall, N.C., 1905.

Smith was allowed to make a public statement before being hanged out of sight of the crowd.