By S. Ani Mukherji

I. Unsettling Beauty

“…a historical materialist views [cultural treasures] with cautious detachment. For without exception the cultural treasures he surveys have an origin which he cannot contemplate without horror. They owe their existence not only to the efforts of the great minds and talents who have created them, but also to the anonymous toil of their contemporaries. There is no document of civilization which is not at the same time a document of barbarism. And just as such a document is not free of barbarism, barbarism taints also the manner in which it was transmitted from one owner to another.”

Walter Benjamin, “Theses on the Philosophy of History” (1940)

Some stories are clearly etched into the landscape. And some aren’t.

I came to Grundy County, Tennessee to see the original location of the Highlander Folk School. For the first three decades of its history, from 1932 to 1961, Highlander operated out of a house in the small town of Monteagle. Here, founders Myles Horton and Don West brought together thousands of workers and organizers to build movements for economic and political democracy. At first, this renowned center of political education focused on working with Southern labor organizers, militant radicals, and Grundy County locals to develop visions and practices of social transformation. By the 1950s, Highlander turned its efforts to supporting the growing civil rights movement. Among its teachers, students, and visitors in this period were freedom struggle leaders Rosa Parks, Septima Clark, Diane Nash, John Lewis, and Dorothy Cotton. I wanted to see the roads, hills, and buildings that these organizers moved through and inhabited. I wanted to know if there were any remnants of the school—physical or ethereal—to be found in this rural county on the Cumberland Plateau.

But there was little at the site. Just a roadside sign noting Highlander’s former location, a few houses, and fields. So I continued driving east, down the road toward Tracy City. Just past the small town’s center, I followed a sign for Grundy Lakes, a scenic spot that is part of South Cumberland State Park. I entered the park and circled the two small lakes on a paved path, passing a hiker and a young couple casting lines into the water while leaning on a pickup truck parked on an embankment between two lakes. The crisp air and clear light—it was January—created an unsettling serenity. Unsettling because of what I was about to learn: these lakes and the land around them are places of terrible histories and incongruous beauty.

At the small lot overlooking the lakes, there are two historical markers. The first tells the story of “Prison Labor at Tracy City.” It explains that the lakes are flooded coal mines that were once worked by imprisoned laborers leased out by the state to the Tennessee Coal, Iron, and Railroad Company (TCI): “It’s hard to imagine that this tranquil landscape once resembled a scene out of Dante’s Inferno…[where] coke ovens belched out dense clouds of smoke as convict laborers stoked, tended and cleaned them, or toiled in adjacent mines.” The sign calls attention to the visible remnants of the brick coke ovens that dot the hills rising from the lakes, explaining that from 1871 to 1896, up to 500 imprisoned laborers, mostly Black men, could be found here at any given time. (Free miners, almost entirely white men, also worked at Tracy City. But the most dangerous and punishing work, such as working the coke ovens, was tasked to Black miners.) Public archeologist V. Camille Westmont has started a project to unearth the history of the mines and the nearby stockade that housed the prisoners. She notes that the annual mortality rate for prisoners was just under ten percent. Perhaps as many as 800 people are buried in the land around Grundy Lakes. Westmont is working on finding the graves.

Just feet away from the marker relating this ghastly history is another that memorializes the “Lone Rock Coke Ovens” as a source of prosperity in a familiar language of local boosterism and modernization. Industrialist Arthur St. Clair Colyar is celebrated as a “skillful promoter” who seized the opportunities of the postbellum South to build the coal mines at Tracy City. The sign doesn’t note that Colyar was, as I later learned, a former slaveowner who was accustomed to profiting from unfree labor, or that he supported the system of convict leasing as a deterrent to collective action and strikes. No connection is drawn between the two signs. The implied balance of perspectives created by cleaving the history of violence and the history of prosperity is farcical. Here, as elsewhere, these stories are inseparable.

II. Larger Histories

“…yet it certainly would be but a charitable assumption to believe that the day is not remote when in every such region, the sentiment of the people will write, over the gates of the convict stockades and over the doors of the lessees’ sumptuous homes, one word: Aceldama—the field of blood.”

George W. Cable, quoted in W.E.B. Du Bois, Black Reconstruction (1935)

I spent the afternoon wandering around the lakes with my camera. When I came home from my trip, I started to dig deeper into the history of this place. I wanted to know what else was obscured or erased from this landscape.

I found stories that those signs only hint at.

The historical marker about prison labor notes: “In August 1892, Tracy City free miners, who opposed the use of prison labor because they wanted the jobs being done by the convicts, burned the stockade and sent the convicts back to Nashville on a train.” This is true. But it is only a sliver of a larger event—Tennessee’s Convict Lease Wars.

The 1892 raid at Tracy City was part of a wave of direct action in eastern and middle Tennessee. A year earlier, free miners in eastern Tennessee had led similar raids to disrupt the system of convict leasing. This system was critical to the state’s postbellum economic and social order. Historian Karin Shapiro argues that convict leasing “primed the economic pump of a pivotal extractive industry—coal mining—upon which many other industries depended.” More importantly, it undercut the position of free miners and helped enforce a racist order through harsh penalties imposed on African Americans for petty crimes. In Black Reconstruction, W.E.B. Du Bois identified convict leasing as a system “for deliberate social degradation and private profit.” From its inception, miners used a variety of methods to oppose the system—forming political alliances, advancing legal appeals, and calling strikes.

After the 1892 raid, the use of convict labor at Tracy City continued. But so did the free miners’ military drilling. In April 1893 they raided the rebuilt stockade with shotguns loaded with BBs and buckshot, killing one guard and wounding several others. By 1896, the combination of worker sabotage, political lobbying, and continued organized attacks led to the end of Tennessee’s system of convict leasing.

Starting in 1891, thousands of workers took up arms in a series of raids to interrupt production, increase costs for the company, and end the use of convict labor in coal mines, a history that Neal Shirley and Saralee Stafford tell in their history of Southern insurrections Dixie Be Damned. Larger waves of action often started with particular local grievances. In the summer of 1892, the TCI reduced hours to halftime for free miners at Tracy City and refused to negotiate. The free miners called secret meetings, and then began military drills to prepare for a raid intended to stop production. Early in the morning on 13 August 1892, more than one hundred armed men marched from Tracy City toward the coal mines. When they arrived, the marchers overran the guards, removed materials inside the stockade, and torched the building. According to one eyewitness, the prisoners helped: “I saw the convicts pouring coal oil [on the stockade] from a gallon bucket.”1 After the stockade was destroyed, the free miners commandeered a train and put 390 prisoners in cars bound for the state penitentiary in Nashville. Along the way, a number of prisoners escaped from the train. Two were shot. Others made their way to freedom, at least for a while.

III. Landscapes Made and Remade

“The visible landscape is not a full record of history, but it will yield to diligence and inference a great deal more than meets the casual eye. The historian becomes a skilled detective reconstructing from all sorts of bits and pieces the patterns of the past.”

D.W. Meinig, “The Beholding Eye” (1979)

The mines at Tracy City continued to operate for two decades after the end of convict leasing. A newspaper from the time describes “blackened creek waters, bleak hills, coke ovens, and blasts of hot air, general unsightliness…barrenness and blackness everywhere. The earth has been stripped of its growth, and coal dust has made dingy everything.”2 Only once the mines were exhausted were they abandoned by the TCI; at that point the company donated the devastated land to the state of Tennessee. In the 1930s, the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) flooded the mining pits to create lakes, planted trees around them, and cut a trail into the land, creating the recreational area that exists today.

Organizers and educators Myles Horton and James Dombrowski from the nearby Highlander Folk School would have witnessed this transformation. They were a few miles west in Monteagle, organizing local workers including CCC laborers. For Horton, organizing meant being in conversation with and getting to know a community and its people. His vision of political education was a collaborative project of “unlearning and relearning.” In his autobiography, Horton described a protracted and dynamic educational process of entering into a circle of learners to help people “to respect and learn from their own experience.” Often this was a literal circle of people in a room together. The model drew both from his experiences with religious education, Danish folk schools, and reading Karl Marx and Vladimir Lenin. He remembered that it was Lenin’s writings that convinced him to adopt a strategy for change based on workers seizing power for themselves: “the people have to win the revolution themselves before it’s theirs. If it’s given to them or if it’s arrived at through compromise, then it’s going to run on a compromise basis.”

Dombrowski combined this type of learning with more formal attempts to understand the community in Grundy County through historical research, interviewing residents about their memories, and then confirming these against company records and newspapers.3 One result of these investigations was Fire in the Hole, an unpublished book-length manuscript finished in 1941. Dombrowski conceived of the work as a regional story of the struggle for democracy—defined as “the right of every citizen of the state to achieve the fullest possible development of all the latent resources of his being”—in Tennessee’s coal country. To try to get a better sense of the histories of violence and struggle in Grundy County—that is, to gather “all sorts of bits and pieces”—I ordered a photocopy of the manuscript from the archives of Highlander records.

What stands out about Fire in the Hole is its historical analysis of the political culture of the Cumberland Plateau, the arrangement of forces of capital and labor, popular authoritarianism and anti-authoritarianism. The fact of poverty in the region had already been well-documented. The short film People of the Cumberland (1937), for instance, portrayed the hardships and endurance of the people of Grundy County. Fire in the Hole went deeper to track the influence of banks, business leaders, the press, and the Ku Klux Klan, as well as the organized resistance of labor unions and the local culture of opposition. Dombrowski wanted to understand the sources of poverty. He also wanted to sketch out the possibilities for transformation and present them in those circles of unlearning and relearning at Highlander.

The history of the Convict Lease Wars riveted his attention. It wasn’t just the stories of coordinated rebellion to confront the TCI and the state. Dombrowski took care to record all the ways that the local community supported the miners. He told of the miners’ wives and children taunting the soldiers called in by the governor with improvised ditties. He recounted the tale of a woman who clothed, fed, and sheltered escaped prisoners and miners hiding out in the woods after a raid. It isn’t hard to surmise how Dombrowski envisioned these local experiences as fuel to help imagine working people winning a revolution for themselves.

The lives and actions of the prisoners, however, remained on the periphery of Fire in the Hole. This is somewhat surprising since Highlander was, from the beginning, dedicated to a vision of interracial organizing. And Dombrowski didn’t hide evidence of racism on the part of Grundy County’s white community. He quoted a longtime resident, who recalled the Black residents of Tracy City being run out of town in the 1880s; and census data for the county in the postbellum period is consistent with the patterns typical of sundown towns.4 Fire in the Hole’s near silence on the quarter-century history of prisoners’ lives was most likely a matter of method. Dombrowski wanted the book to reflect the experiences of the local people who he met in the 1930s. And populations, like landscapes, are products of history. Just as the CCC erased the ugliness of the landscape, the free miners’ memories offered little evidence of the struggles of those who didn’t stay or those who didn’t survive.

IV. What People Do to Get Free

“But slavery didn’t end just because [Frederick] Douglass gave really good speeches. Slavery also ended because Douglass beat Mr. Covey back on the plantation and he said, I’m never going to get hit again. You’ll have to kill me first. Recognizing the diversity of tactics for our freedom is so important and it’s not typically what we’re taught as children. So how do we show a more robust, interesting, exciting, accurate history of what people did to get free?”

Derecka Purnell, “Reclaiming the Power of Rebellion” (2021)

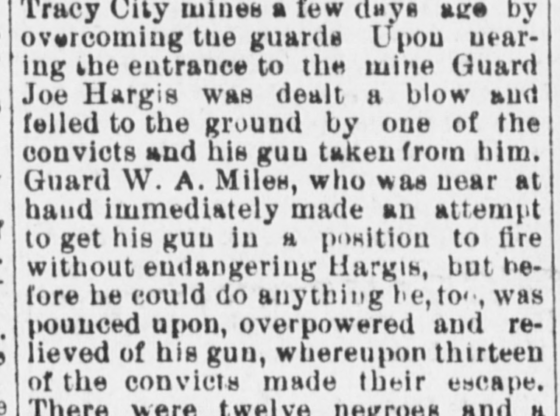

Tennessee newspapers give some glimpses of prisoner life and resistance at Tracy City. In 1882, the Knoxville Daily Chronicle noted that two prisoners, Jim Mills and Jones Whitaker, died running away from Tracy City. The Bolivar Bulletin informed readers that prisoners tried to escape in March 1885 while being marched from the stockade to the Lone Rock Mine. After the 1892 raid and burning of the stockade at Lone Rock, reports of escape attempts increased. In March 1893, thirteen prisoners—twelve Black and one white—escaped. Another six prisoners, all Black, escaped in March 1894 according to Johnson City’s The Comet.

It is notable that these reported escapes were usually in groups. They were collective actions. Though there are no direct accounts from prisoners, there are hints about how a sense of unity and shared struggle was fostered.

One source is Dombrowski’s research. The manuscript for Fire in the Hole includes a white miner’s memory of the work ballad “Lone Rock Song,” a story of violence, wicked guards, and a villainous “bank boss” that was sung by Black prisoners. The lyrics mourn a miner worked to death with an undernote of simmering contempt for those responsible. Based on the miner’s ability to recount the lyrics, it must have been sung over and over while prisoners fed coke ovens and entered the tunnels into the mines at Tracy City.

Records of charity can also offer clues about prisoners’ lives, when read against the grain. In 1884, the Home Journal of Winchester, Tennessee published a minister’s request for donations of reading materials for prisoners at Tracy City with the note: “They need it, and are eager for it.” The first part of this sentence carries a note of condescension. But the second part about an eagerness for reading material summons the long history of education and captivity that allows a picture to form of imprisoned men reading to each other in the stockade, thinking together about the news, and its meanings.

Reading together, singing together, grieving together, planning escapes together. Unlearning and relearning in conversation. These collective experiences of the prisoners at Tracy City likely paved the way for the boldest organized act of prisoner opposition to convict leasing. In July 1894, seventy-five prisoners conspired to load a cart with dynamite, set a fuse, and send the bomb into the mine. The explosion injured two guards and killed a deputy warden. The prisoners then held the mine for a day before the uprising was suppressed. As much as the free miners’ raids in 1892 and 1893, this event exemplified the type of collective “capacity of the people to work together for good” that Dombrowski and Highlander wanted to recall and build on. It also modelled the slow work of building up potential followed by collective action to get free.

There is no hint of this story in the visible landscape at Grundy Lakes today. No marker, yet, that memorializes this moment of uprising and connects it to histories of violence, organizing, struggle, and erasure, both local and global. Looking out onto the water on that winter day, I saw only the reflection of hills and woods. But I also felt the potential for more.

Archival Sources

“The Attack of the Grundy County Crusaders on the Highlander Folk School (18 December 1940),” in box 33, folder 5 of the Highlander Research and Education Center Records, Wisconsin Historical Society.

James Dombrowski, “Early History of Grundy County, c. 1940” in box 52, folder 11 of the Highlander Research and Education Center Records, Wisconsin Historical Society.

James Dombrowski, “Fire in the Hole, c. 1940” in box 12, folders 9-10 of the James A. Dombrowski Papers, Wisconsin Historical Society.

Notes

[1] This quotation is from an oral history taken by James Dombrowski; it appears in his unpublished book, Fire in the Hole, discussed below.

[2] Quoted in Dombrowski, Fire in the Hole.

[3] Folklorist Archie Green praised Dombrowski’s oral history methods in his study of coal-miners’ songs, Only a Miner, reproducing Dombrowski’s interview notes as useful guide for other labor historians.

[4] Historian Jeanne Theoharis’s The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks describes the awkwardness of Highlander bringing freedom struggle organizers to a sundown county. Theoharis quotes Parks recalling her unease while travelling to Grundy County: “I found myself going farther and farther away from surroundings that I was used to and seeing less and less of black people. Finally I didn’t see any black people and was met by this white person.”

AUTHOR BIO

S. Ani Mukherji is an associate professor of American Studies at Hobart and William Smith Colleges in Geneva, New York. He is interested in political culture, radical history, and place. His writing has been published in the Boston Review, American Communist History, and the Journal of Academic Freedom. He spent his youth in Tennessee and southern California.

Article image courtesy of chroniclingamerica.loc.gov

Article image courtesy of chroniclingamerica.loc.gov