By Jessica Hatrick, Audrey Beard, Warren Wagner, Lucien Baskin, and A. Naomi Paik

Jessica Hatrick (she/they): I’m part of USC Abolition, which is the abolitionist collective at the University of Southern California. We emerged in the summer of 2020 out of an interest in the graduate student workers organizing collective in addressing abolition on campus. As an undergrad at UC San Diego, I was a part of Students Against Mass Incarceration, which emerged in 2013 and is still in existence and active.

Lucien Baskin (they/he): I work with Free CUNY, which is an organization of students, community members, staff, and faculty across the City University of New York (CUNY) system and in New York. Free CUNY organizes for a tuition free university, but one that is also free in a larger sense of being free of cops, free of all connections to the carceral state, and to make institutions a place where people have access to free housing, food, and transportation throughout the city. We got connected to the Cops Off Campus Coalition last year during the buildup to Abolition May, in an effort to connect our struggle to larger abolitionist struggles throughout Turtle Island.

Warren Wagner: I organize with Care Not Cops, which was formed in 2018. After our peer and friend, Charles “Soji” Thomas, a Black student undergoing a mental health crisis was shot by the University of Chicago Police Department (UCPD), Care Not Cops was formed both to support Soji and to organize for the defunding, and the redirection of investments from policing into mental health care and support for students and communities of color. The organizers who initially started that had been connected to a lot of different struggles. One was Students for Health Equity, which was part of the effort to bring a Level 1 Trauma Center to U Chicago Medicine in order to treat injuries like bullet wounds and car crashes. Since then, we did a participatory defense campaign for Soji, and finally got his charges dropped in the beginning of last summer. Since then we’ve just been building abolition in the greater Hyde Park, Woodlawn Kenwood area, specifically with a focus on UCPD, but also the Chicago Police Department (CPD), we’re against the off-campus cops, too.

A. Naomi Paik (she/her) : This year, I just moved to University of Illinois Chicago (UIC) where there is Abolition UIC, after being at University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (UIUC) with Defund UIPD, an organization that emerged out of the wake of George Floyd’s execution and the mass mobilizations against policing. What instigated it was that at one of the George Floyd protests in town, the Champaign Police Department started tear gassing the youth and arresting and beating them up. UCFTP’s Abolition October was also something that we wanted to be in coalition with. So we started organizing events or mobilizations in line with their launch of UCFTP (an anti-policing coalition at the University of California). What’s unique about UIUC’S campus is that it’s a small university-hospital city, and it’s divided between two town jurisdictions, and we’re also in a county. So there’s four or five different police agencies that have jurisdiction. And the second largest police force in the county is the University Police Department. So they have this inordinate size and scope for the size of the community, and it’s also where the SWAT team is housed. So we do feel that the UIPD is a clear target. UIUC is the main employer and the biggest institution in the area. If it’s claiming to be a community leader, it needs to take the lead on dismantling violent structures.

Audrey Beard : Starting in 2019, I was organizing with Rensselaer for Ethics and Science, Engineering, and Technology. In early 2020 there was a New York State Senate bill, SB 7645, which was specifically tailored to allow Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (RPI) to grant peace officer status to university police officers, which would have granted them, among other things, the right to use lethal force and conduct warrantless searches on and near RPI property. That started a lot of student activism around investigating what property RPI owns, and it was a huge amount. They were the largest landowner in the city. That got us thinking about facial recognition technology and security cameras, and it kicked off a lot of activism. I left RPI, in the middle of a PhD program, and then linked up with the Cops Off Campus Research Project, and through organizing with them, I heard about the Cops Off Campus Coalition.

Jessica

USC has its own private police force, the Department of Public Safety (DPS), who pride themselves on being one of the largest campus police forces in the country and have over 300 employees. Their patrol zone is an area that’s about four or five times the size of campus, which means that the surrounding communities–we’re in a historically Black and Brown neighborhood–are being policed by DPS, the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD), and the LA Sheriff’s Department. Alongside this, USC perpetuates a belief that the the area surrounding the campus is “dangerous” in order to justify the further funding of their police force. For example, when I started here, one of the things I had to do before I was allowed to register for classes was a gamified, “how to be safe on campus” training, and one of the ways you failed the game was if you went south of campus after dark, because that was too “dangerous.” We have a good amount of high schools surrounding us that are primarily attended by Black and Brown folk, and campus police will stop those students and ask them why they’re on campus. This is pretty different from my undergrad experience where UC San Diego was purposely built in a predominantly white neighborhood with various racial covenants. At UC San Diego it was primarily Black and Brown students who were being policed within the surrounding neighborhood and told they didn’t belong there. We’ve also seen on our campus how COVID has been used to further justify this hyper surveillance and reinforce the boundaries between the campus and the surrounding community.

Lucien

One piece of the carceral landscape of CUNY is the role of carceral education and the reality of recruitment in the university that is connected to the diversity of the institution. For example, the CIA chose CUNY’s Baruch College, which is one of the most linguistically diverse colleges in the country, as the first school to roll out its Training Program pilot, because that “diversity” was an asset that they wanted to tap into. Similarly, CUNY’s John Jay College of Criminal Justice, which is an Hispanic Serving Institution, has a major in Homeland Security that is essentially just an ICE training program.

Much of our work is grappling with the contradictions of being in an institution that lies at the intersection of organized violence and organized abandonment, and thinking about what abolitionist presence looks like in that space, where we’re struggling against a prolonged assault on CUNY that includes constant budget cuts, program closures, layoffs, and infrastructural decay. At the same time we are trying to struggle within it to make it more of a life affirming institution, rather than one that’s rooted in policing, prisons, and war.

Warren

The carceral landscape of U Chicago is definitely rooted in its private police department, which is either the second or third largest private police department in the country. They have guns, tasers, arrest power, their jurisdiction goes way further off campus, which is primarily where they patrol. The way a lot of us think about this is that it is in engaging in its own really particular settler colonial project on the South Side, because it’s based a lot around protecting property and making the neighborhood more appealing to wealthy students, parents, alums, donors, etc. For example, in 2008 they got consulting from The Bratton Group, which is a consulting firm led by William Bratton, who was Commissioner of the New York Police Department and Chief of the LAPD and who implemented stop-and-frisk and the broken windows theory of policing. We see the police protecting this hugely resourced institution in a surrounding neighborhood that’s faced the brunt of white supremacy, segregation, and huge urban renewal efforts by U Chicago and other parties in the past. And so the policing is only the tip of the spear. And that carceral landscape goes along with how they distribute health care, how they distribute community engagement, loans and grants and things. It’s always the most means-tested, always going to small businesses and really professionalized nonprofits, never directly to people.

Audrey

Myself and Brendan from the Cops off Campus Research Project, gave a presentation to carenotcops outlining the property purchases of University of Chicago. We found that in the years after the University of Chicago dramatically increased their police patrol jurisdiction, they made something like 90% of their dozens of annual property purchases within that policing jurisdiction. The remaining purchases were in rapidly gentrifying areas like Wicker Park and Logan Square; they were quite literally acting as a tool of gentrification, colonialism, displacement, and dispossession. This research is consistent with a lot of what the Cops Off Campus Research Project does. We try to give activists in local communities the tools to conduct this sort of research. And what we’ve seen time and again is that universities follow this pattern exactly. They quite literally act as a gentrifying force by purchasing private property near or around the institution. They expand their policing jurisdiction to cover their investments. And then, once they expand, they continue to purchase within that jurisdiction. And if they’re not doing that, they usually purchase in places where they see a quick return on investment. As Nick Mitchell argued[2] , they’re diversified holding companies, and to pretend that they are not is to play into this giant charade that that they’re putting up.

Jessica

One of the ways we’ve seen policing interact with questions of housing justice and reproductive justice on the USC campus is in the experience of Kayla Love and her partner, Khari Jones. In June 2021, Love gave birth to their first child. While they had a home birth, some medical complications required them to go to the hospital at the last minute to seek care for Love. After their daughter was declared healthy by paramedics and deemed to require no immediate/emergency services, they chose their legal option for her to be seen by her primary care physician the following day and returned to their apartment in graduate housing. The hospital called social workers, and that same evening the social workers showed up with thirteen armed LAPD officers at their apartment. Upon arrival an officer pointed a gun at Jones before arresting him, leaving him handcuffed for two hours outside their apartment. Social workers and officers repeatedly returned to their home until the story received media coverage, at which point they stopped. Their story shows how the hyper-policing on this campus and in this community disproportionately affects Black students and community members, but it also shows how policing, social work, healthcare, housing, and universities all intersect in their construction of “safety”.

Warren

Two other campaigns have included demands for, first, a student- and community-led Ethnic Studies department that would have slots free or even paid slots open for neighbors to take classes, positions of paid like local organizers and artists and residents. This would be a place for horizontal, non- hierarchical learning and also a place of practice, not just theory. And the second campaign is for student-led centers, such as the Assata Shakur house, Grace Lee Boggs house, and Sylvia Rivera house to replace the current Center for Identity + Inclusion. These liberatory, autonomously run, community centers could also be a point for healing the massive violence that the university as a whole has put on to the community. They could be places for forging the shared future together. And another connection is to anti-gentrification struggles. Since policing, gentrification, and displacement are so connected, especially at UChicago, we’ve always demanded the university cease all new property acquisitions and restrict the UCPD boundaries to the main campus. As a mainly student group formed in 2018, we’ve been educated by neighborhood abolitionist groups such as the No Cop Academy campaign, the #LetUsBreathe Collective, Assata’s Daughters, and GoodKidsMadCity. They have collectively taught us that if it weren’t for the constant tax of white supremacy and capitalism, the South Side would be thriving, that these abolitionists tools have already been built in the neighborhood, and that communities already know what they need for safety. Policing and gentrification are two of those main axes where we just need to stop the attacks on the communities, and then allow for the self determination of the surrounding communities.

Lucien

In January 2020, in conjunction with the Fuck The Police demonstrations, there was a co-organized event between CUNY students and New York City public school students. This was a speak-out demonstration on the steps of the Board of Education for the abolition of the police in K-12 schools and at CUNY, as well as in the city as a whole. During this event, we particularly highlighted the policing of students and other people on subways and buses, because in a city that is very public transportation reliant one of the main sites of policing for students is not only the university, but also the subways and buses that they take to get to school every day.

Naomi

The COCC emerges out of multiple threads of organizing. Universities have always been a locus of organizing and of protest and of dissent. And that’s why post-Cold War campuses like UCSD have been architecturally designed to disrupt protest, and to not have central areas where students can gather and show their dissent. So, I mean, it’s actually built into the landscape of many of our campuses. We can, for example, look back at the student demands for ethnic studies at SFSU in the late 1960s, which were never just about curriculum. They were always tied to the antiwar movement, to Black liberation, Brown liberation, the feminist movement, and anti-gentrification. They were about having liberation as the goal of education. Rather than worker training, they were always anticapitalist in their critique because they wanted a redistributive economy that works for all people, including working people. The other thing is that the uprisings in response to the murder of George Floyd could not have happened without Black Lives Matter, but it’s not like Black Lives Matter just popped out of nowhere, either. They are also built on the foundations that were built by abolitionist scholars and activists in the 80s and 90s. And then those people were building off the kind of revanchist remains of any kind of liberatory movements that were dismantled during the 1980s. So it’s like there are these genealogies that have brought us to this moment.

from: https://diva.sfsu.edu/collections/strike/bundles/237372

Lucien

We root ourselves in the history of struggle at CUNY. In particular, going back to the open admissions strike of 1969 and the budget struggles of the 1990s have been helpful for understanding the terrain in which we organize. We also use a counter-history of the institution as a subject of political education. So we’ve made zines about histories of organizing at individual campuses, because knowing those histories can be very galvanizing toward struggle.

Warren

I feel like the whole history of a lot of the radical students struggles we take inspiration from are just about democracy, but in a material sense, like actual people having control and self-determination. In one of our political education sessions, we were reading the proposal for the Lumumba-Zapata college at UC San Diego. And one of the points that struck us was that they were talking about how it should be in large part financed by the neighborhoods of color the school was around. And at first we were confused, because why wouldn’t you want to be redistributive? But the point was that the college needed to be accountable to those neighborhoods. We are all necessary to create whatever the university is, so we all have to be fundamentally cared for and a part of building it. Often that means rejecting competition and scarcity and trying to make the university into an actual commons, which it definitely never was, but could be.

Jessica

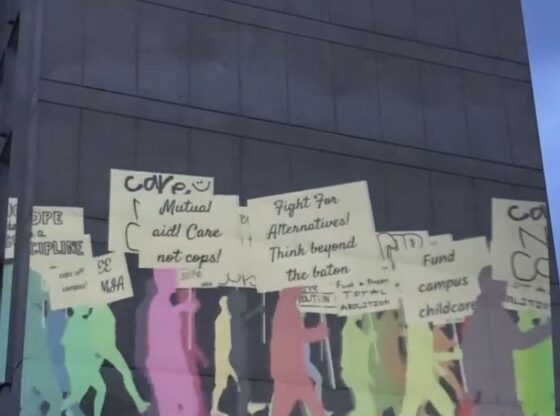

This is at the root of Cops Off Campus’ goal for Abolition Spring. Our 2022 theme was called (Re)Building Community to address how some campuses might be rebuilding with community and some campuses might be building with community for the first time and thinking about this town-gown divide. But also in part this is to highlight the constructive rather than the destructive aspects of abolition and abolition democracy—the building of new things, as opposed to the destroying of the current systems. Though, of course, folks can also burn down their campus cop infrastructure!

AUTHOR BIOS

warren wagner is a student at the University of Chicago studying critical race and ethnic studies and sociology. They help organize for abolition on and around the campus as a part of #CareNotCops, and support other efforts like UChicago Against Displacement.

A. Naomi Paik is the author of Bans, Walls, Raids, Sanctuary: Understanding US Immigration for the 21st Century (UC Press, 2020) and Rightlessness: Testimony and Redress in US Prison Camps Since WWII (UNC Press, 2016). She is an associate professor of Criminology, Law, & Justice and Global Asian Studies at the University of Illinois, Chicago.

Jessica Hatrick is a doctoral candidate in the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Southern California, researching higher education student activism, with a focus on students doing abolitionist work

Lucien Baskin is a doctoral student in Urban Education at the CUNY Graduate Center where they study histories of abolitionist organizing at CUNY. They teach at John Jay College and organize with Free CUNY and the Cops Off Campus Coalition.

Audrey Beard organizes with the Cops Off Campus Coalition and works with the Cops Off Campus Research Project.