*Editor’s Note: This essay is part of the Abusable Past’s “The Border is the Crisis” Series*

“Give me your tired, your poor…,” reads a plaque on the Statue of Liberty. But in July 2019, acting director of the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services Ken Cuccinelli announced the Trump administration’s latest racist attack on immigrants and the poor, adding that the now-mythic message associated with Lady Liberty should be limited to those “who can stand on their own two feet, and who will not become a public charge.”

Under this administration’s new interpretation of an old, broadly construed immigration provision, legal entrants may be denied a green card if they use, or perhaps are just suspected of using, a wide range of government benefits that have historically been available to them and others. Officials could rely on a set of loosely based assumptions to determine whether they were simply too “tired” and too “poor”—to rely on the plaque’s language—to legally stay in the United States, where they have been deemed likely to become a financial burden.

Versions of this are already in place, as it has been for many years, but this move takes aim at detracting would-be eligible people from becoming naturalized and, more broadly, creating an atmosphere of intimidation and hostility during a time of fiscal uncertainty and anti-immigrant fervor. It is, surely, a recipe for violence.

Make no mistake, the “likely to become a public charge” policy has a long racist, classist, and ableist history, and Trump’s administration seeks to exploit it to those ends yet again.

Surely, those histories of racism, classism, and ableism have always been intrinsically tied to sexism and homophobia, and to understand everything at stake with this possible expansion of the public charge clause, we must come to terms with how all those categories have historically coalesced to exclude a wide range of people from entering U.S. borders.

Immigration law in the United States was only federalized in the late 1800s. Prior to that, it was largely controlled by the individual states. State passenger laws first adopted the idea of using discretionary powers to exclude immigrants based on their suspected likelihood for financial dependence. This largely originated as a means to exclude Irish “paupers” and others who immigration officials perceived as undesirable at the time. Variations of this type of restriction were soon articulated in federal U.S. immigration laws in 1882 and 1891. It became national policy.

While the use of the “public charge” clause was certainly connected to class anxieties, it has similarly been dictated by changing definitions of “whiteness” over time. As some immigrant groups gained admission into a privileged category of “white,” others remained racialized and kept from either entering the United States or reaping the full benefits of citizenship.

This was gendered, too. While the “public charge” provision has always been framed as gender neutral, the law, like other institutions of power during at least the first few decades of the twentieth century, viewed women as inherently dependent on men. Should a man be absent, the state might have to step in. Under this sexist logic, single or unaccompanied women trying to enter the United States could be read as likely to become a burden to the state and therefore excludable.

Single or unaccompanied Black women from the Bahamas were often denied entry at the port of Miami in the early 1900s, for example. In relying at least partially on a long-existing, racist narrative of linking Blackness to sexual perversity, immigration officials often suspected these Black women of being prostitutes and therefore deemed likely to become a public charge. A Miami newspaper noted in 1919, “every boat from the Bahamas brings in undesirables that are bound to become charges and a public nuisance.”

While most of these cases are not known to us today because it proved difficult and expensive to challenge them, one case reached all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. Unmarried and pregnant, Isabel González sailed from her native Puerto Rico in 1902, or fifteen years before Puerto Ricans would receive U.S. citizenship. A similar racialized mythology that made assumptions about women of color, their sexual pasts and morals, and dependency, found immigration officials in New York deeming her likely to become a public charge.

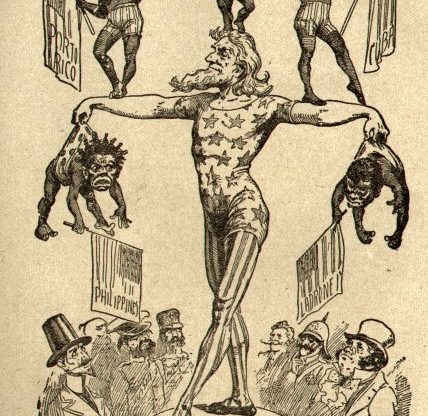

This was, among many other things, a question about U.S. empire. It was not uncommon for cartoons of the day to portray lands under U.S. control, such as Puerto Rico, Cuba, or the Philippines, as racialized children or women incapable of self-rule and requiring the assistance of a stern and patriarchal Uncle Sam. In many ways, González appeared to be a metaphor for Puerto Rico herself.

González fought her exclusion at the U.S. borders and forced the nation’s highest court to weigh in on the citizenship status of all Puerto Ricans and the many others caught in the middle of the United States’s much more aggressive imperial turn. The court ruled she was neither an “alien” nor a citizen. In the end, she was allowed to enter and stay, and her activism helped pave the way for U.S. Congress to extend all Puerto Ricans citizenship in 1917.

Just the same, as this history demonstrates, the “public charge” provision could be used to exclude a wide range of people who fell outside a constructed white, cisgender, and heterosexual ideal. In 1952, U.S. Congress passed legislation to specifically exclude homosexual foreigners from entering the country. That exclusion was officially the law of the land until 1990. But before the 1950s, or before the rise of modern lesbian, gay, and bisexual identities, immigration officials could discretionarily use the broad “public charge” clause to bar those who engaged in same-sex acts or whose bodies were viewed as somehow “perverse.” This was largely premised on the idea that those who practiced sodomy, had committed an act of moral turpitude (which similarly had an expansive definition), or those flagged as having anatomical differences not traditionally associated with the sex assigned to them at birth would eventually be incarcerated or institutionalized and therefore burdens to state resources.

What ties all these examples together—both then and today—is that they rely on preconceived notions of people based on their place of origin, race, class, gender, sexuality, ability, and age. No doubt, if the Trump administration’s expansion of this policy survives the legal challenges it already faces, it will, like before, cast an even wider net than most people may realize; it will further criminalize and punish the poor, people of color, gender and sexual minorities, and many other marginalized groups.

One need not work too hard to find parallels in these histories and the racist mythologies of the present and not-so-distant past of the state-suckling “welfare queen” or “anchor baby” coded as Black and Brown. In fact, the architects of this policy’s latest incarnation are betting on it.

AUTHOR BIO

Julio Capó, Jr. is associate professor of History and the Wolfsonian Public Humanities Lab at Florida International University in Miami. He is the author of the award-winning Welcome to Fairyland: Queer Miami before 1940 (UNC Press, 2017) and the curator of the Queer Miami: A History of LGBTQ Communities exhibition at HistoryMiami Museum. A former journalist, he has published in Time, Miami Herald, the Washington Post, and other media outlets.

An 1899 political cartoon depicts Uncle Sam "holding up" racialized representations of individuals from parts of the world subjected to US imperial intervention at the turn of the 20th century. Courtesy of the Philadelphia Inquirer.

An 1899 political cartoon depicts Uncle Sam "holding up" racialized representations of individuals from parts of the world subjected to US imperial intervention at the turn of the 20th century. Courtesy of the Philadelphia Inquirer.