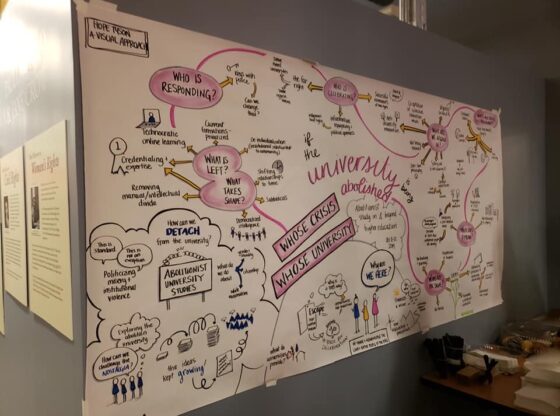

Cover image: graphic recording by Hope Tyson from the 2019 conference “Whose Crisis? Whose University?: Abolitionist Study in and Beyond Global Higher Education” image by Abbie Boggs

By Liz Montegary

In the opening lines of their “invitation” to “Abolitionist University Studies,” Abigail Boggs, Eli Meyerhoff, Nick Mitchell, and Zach Schwartz-Weinstein anticipate some of the anxieties their proposal might incite. Specifically, they acknowledge that some might think it unwise to talk about the university in abolitionist terms when rightwing forces in the US seem hell bent on demolishing universities, public education, and the very idea of public institutions. What if this approach gave the Right more “ammunition” in their “assaults” on higher education? By acknowledging this anxiety, they implicitly draw attention to the sentiment that seems to drive much of the work that has emerged under the rubric of critical university studies: the sense that leftist academics are obliged to defend the university.

This is something I’ve been thinking about quite a bit lately – in part, as an increasingly active member of my campus’s union – but also, in relation to an article I’ve just finished on rightwing attacks on gender and sexuality studies. I believe there is a great deal to be gained by engaging with far-right political discourse and, specifically, ultraconservative accounts of the US academy. Though, as a queer cultural studies scholar who writes about US homonormativities, I initially felt ill-prepared to study rightwing critiques of my field and the academy. I was trained to focus on the racist and capitalist logics facilitating neoliberalism’s strategic incorporation of gender and sexual diversity and queer and feminist knowledges. With the turn of the twenty-first century, queer studies appeared to have moved beyond worrying about the Right’s relentless homo- and trans-phobia: rather than wasting analytical energy on blatantly repressive forces, the field focused on developing frameworks for apprehending the subtler and more flexible modes of control operating under the signs of “equality” and “inclusion.” Faced with the recent and rapid rise of far-right movements in the United States and around the world, I now have a different understanding of the task of queer cultural studies, and I am working to expand my critical capacities. I am convinced our political analyses will be stronger if we take the time to decipher the terms and grammar structuring conservative critiques. Moreover – and more directly related to abolitionist projects – I think a closer look at the Right can put a productive pressure on leftist analyses: a pressure that challenges any nostalgic attachments or ethical obligations to the university and that demands more imaginative (and perhaps riskier) responses. [1]

My article, “Anti-Gender, Anti-University: ‘Gender Ideology’ and the Future of US Higher Education,” [2] takes a single figure as its starting point: Robert Oscar Lopez, a Brown, formerly bisexual, and openly conservative Christian literary scholar who overcame his queerness after “miraculously” falling in love with a woman and becoming a husband and father. As a tenure-track and then tenured English professor at California State University-Northridge (CSUN), Lopez wrote extensively about “liberal academic tyranny,” publishing nearly fifty essays about the alarming state of US higher education on conservative online platforms between 2012 and 2016. This body of work, I argue, reveals much about the broader alignments that have occurred within American conservatism in the recent past and about the racial and sexual anxieties underlying rightwing attacks on the academy. While I’ll touch on these themes in my contribution to this forum, I’d like to focus here on the shift that takes place in Lopez’s thinking on higher ed over time and, specifically, his eventual decision to distance himself from the university. I think a consideration of his ostensible pivot away from the academy can help us better apprehend the Right’s seemingly destructive impulses and better appreciate the place abolitionism might play in leftist struggles in and around the university.

Lopez’s initial foray into writing about the academy seems to have been inspired by the backlash he experienced upon gaining visibility as an outspoken opponent of marriage equality. While admittedly not the most well-known, Lopez was certainly one of the most vocal opponents of same-sex marriage and parenting in the United States. He first garnered attention for his anti-LGBT advocacy in August 2012 when he published an essay about the “horrors” he endured growing up as the child of a lesbian mother. Over the next few years, in addition to submitting testimonies in defense of “traditional marriage” to same-sex marriage hearings at the state and federal levels, he participated in “anti-gender”/“pro-family” organizing efforts in the United States and across Western Europe. His work landed him on the anti-hate watchlists of organizations like GLAAD and the Human Rights Campaign, which prompted a number of scholars and activists to contact his university and demand he be fired. Although CSUN took no action against him and ultimately promoted him with tenure, Lopez leveraged this experience in his writing about the plight of conservative professors and conservative thought more broadly in the US academy. These earlier essays on higher education are firmly rooted in familiar “campus culture war” arguments. Even as he lamented the demise of the liberal arts in the face of queer theory and ethnic studies – and likened campuses to “left-wing police states” run by “hypersensitive” “screeching lunatics” trying to “silence” conservative scholars in the service of “liberal indoctrination” – he held out hope for a return to teaching the classics, family values, and the “foundational virtues of our republic.”

In mid-2015, Lopez’s analysis of and attitude toward the academy changed dramatically. The impetus for this shift seems to be the fact that a student filed a Title IX complaint against him for promoting homo- and trans-phobia and creating a “hostile learning environment.” Although the resulting investigation cleared him of these charges, he was found to have retaliated against the student and was instructed to await the administration’s disciplinary decision. [3] Over the next six months – as he enjoyed a few minutes of fame as the cause célèbre of some far-right news outlets – Lopez continued writing about the university, but the target of his critique shifted from specific identity-based fields to higher education as a whole. Infusing longstanding American hostility toward the university with the rhetoric of the global “anti-gender” movement, he began claiming that the academy had been taken over by what he called, variously, “gender insanity,” “sexual radicalism,” and “diversity fascism,” projects he indicted as serving the interests of whiteness and further marginalizing people of color (including bisexual Latinos like himself). The uncritical embrace of “LGBT ideology,” he argued, was adversely affecting the ideological as well as the racial and ethnic diversity of the university: the repression of conservative Christian thought amounted to a form of oppression that disproportionately impacts Black and Latino students and professors who, according to Lopez, tend to hold “traditional” values. While there is certainly more to say about the use of diversity rhetoric to prop up conservative agendas, [4] I want to flag the way Lopez leverages his critique of “gender-fixated social justice warriors” (like the student who filed the complaint against him) to denounce higher ed. Aligning himself with critics on the Right, Lopez holds up the “thought policing” behavior of “hysterical” students and “bloodthirsty” Title IX administrators as evidence of the fundamental dysfunction of the university.

Lopez’s disillusionment with the academy eventually culminated in his late 2016 demand that the federal government defund colleges and universities and “shut down higher education as we know it.” Significantly, Lopez’s turn away from the university coincided with two events: first, his resignation from CSUN and move to a Baptist seminary in Texas [5]; and second, the 2016 US presidential election, which further evidenced the global resurgence of far-right pseudo-populisms. In what was likely an effort to gain credibility in ultraconservative circles, Lopez began claiming an expert “outsider” position. Touting his newfound distance from the university, he took up a popular rightwing position, declaring universities useless and degrees a waste of time and money. Notably, rather than basing such claims on solely anti-intellectual sentiments, Lopez, like other conservative critics, pointed to rising tuition costs and ballooning student debt (which he blames on the greed of tenured faculty and the willingness of Democrats to fund federal loan programs) and to the declining quality of education today (which he attributes to the exploitative labor system saddling adjuncts with the bulk of instructional labor). These newer critiques bolster conservative depictions of the university as the epitome of liberal hypocrisy and of public education as serving the amoral partisan interests of the Democratic Party. It is from this newly contrived vantage point that Lopez abandons the university. In addition to calling for an end to federal funding, he advised parents to send their children to private Christian institutions or two-year trade schools. Higher ed, he provocatively suggests, may not have a place within conservative culture or rightwing platforms.

What strikes me about this pivot away from the academy is the willingness to reject what Boggs, Meyerhoff, Mitchell, and Schwartz-Weinstein refer to as the university’s claims to “a priori goodness” and its “appearance of necessity.” Lopez severs his material ties and nostalgic attachments to the institution and joins the far right in questioning whether we should presume the continued existence – let alone relevance – of the university. Such a move suggests, at first glance, a degree of political risk-taking and creativity rarely seen on the left. As such, it might be worth taking note of the Right’s will to imagine otherwise. That said, I have no interest in glorifying these rightwing refusals. Turning away from a particular institutional form does not disrupt the settler colonial and racial capitalist regimes of accumulation that made possible and are made possible by that institution. Far from an abolitionist project, the embrace of private faith-based and vocation-focused schools might be better understood as an attempt to secure a foothold in a newly configured educational landscape that values job readiness and technical training above all else. [6] Furthermore, the Right, Lopez included, isn’t actually turning its back on the university: the academy remains a key battleground for ultraconservative forces in the United States. Tellingly, Lopez often hedged his calls for defunding academia by clarifying that he specifically recommends withholding federal monies from institutions hosting degree programs in critical ethnic studies or gender and sexuality studies. As such, his “anti-university” performance participates in a wider effort – not to abolish colleges and universities necessarily – but to undermine academic knowledge, especially from fields challenging the ideological underpinnings of white supremacy, classical liberalism, and heteropatriarchal nationalisms. By fostering distrust in and disdain for higher education, conservative attacks on the university’s legitimacy bolster the larger rightwing strategy of creating a robust and respected “parallel academy” – a network of think tanks, professional associations, and privately funded centers and institutes on mainstream campuses – where ideas about race, class, gender, and sexuality that scholars have soundly rejected can be revived as valid social and political theories. [7]

What, then, does a clearer understanding of the Right’s account of the problems with US higher education mean for how we, on the left, engage the university? Well, to begin, I think it puts us in a better position to make a case for why we need to move beyond a defensive framework. After all, the university denounced by the Right is hardly an institution worth defending. The caricature of academia promoted by rightwing forces is not unrecognizable to the left. Conservatives bring into focus (albeit it in distorted ways) progressive concerns about financialized bureaucracies, exploitative labor practices, the warehousing of surplus populations, the limits of neoliberal inclusionary projects, and even the racist and classist operations of homonormativity. Historian Kim Phillips-Fein made a similar observation in her 2019 essay “How the Right Learned to Loathe Higher Education.” Responding to rightwing critiques of the university’s role in maintaining economic privilege, she calls on the university to do more to challenge social and economic inequalities. She urges us to fight for more government funding, to lower tuition and end legacy admissions, to support campus unionization efforts, and to advocate for public education as a fundamental right. [8]

Now, I don’t think an abolitionist approach to the university would necessarily say “no” to the agenda she outlines, but this kind of response is premised on a fantasy of the university as existing outside capitalism and apart from the carceral colonial state – a fantasy in which those who inhabit the university can choose whether to be complicit. In the face of rightwing critiques that ring true precisely because they name the university’s violences, I don’t think we, as leftist academics, can afford to dwell in such fantasies. This is why I’m drawn to an abolitionist university project. Abolitionism gives us a way out of that increasingly unsustainable defensive mode: we can refuse the choice of being either “for” or “against” the university. At the same time, by demanding we seriously reckon with the academy’s historical embeddedness in racialized political economies and policing mechanisms, [9] an abolitionist approach doesn’t let us off the hook. We can neither feign institutional innocence nor pretend we’re capable of abandoning or even distancing ourselves from the enterprise. What abolitionism offers, instead, is a way back in: a framework for thinking newly about the university, how we want to repurpose its resources, and to whom we must hold ourselves accountable.

AUTHOR BIO

Liz Montegary is Associate Professor of Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at Stony Brook University. She is the author of Familiar Perversions: The Racial, Sexual, and Economic Politics of LGBT Families(Rutgers, 2018) and co-editor, with Melissa Autumn White, of Mobile Desires: The Politics and Erotics of Mobility Justice (Palgrave, 2015).

Notes

[1] In their “invitation,” Boggs, Meyerhoff, Mitchell, and Schwartz-Weinstein take issue with “golden age” narratives that portray the academy as thrown into crisis during the late 1970s when outside forces suddenly compelled the institution to abandon its redistributive, democratizing function and align its educational mission with technical expertise and economic efficiency. Aside from obscuring the university’s foundational imbrication in racial capitalism and colonial domination, such depictions gloss over the fact that the institution never actually delivered on its promises of justice. See, also, Abigail Boggs and Nick Mitchell, “Critical University Studies and the Crisis Consensus,” Feminist Studies 44.2 (2018), 432-63.

[2] Forthcoming in Feminist Formations.

[3] For a concise overview of the case against Lopez, see Colleen Flaherty, “Whose Bias?” Inside Higher Ed, Nov 24, 2015.

[4] See Roderick A. Ferguson’s discussion of how counterrevolutionary forces have, since the late 1960s, mobilized discourses of “tolerance” and “diversity” to suppress student protestors (We Demand: The University and Student Protests [Oakland: University of California Press, 2017]). For an analysis of more recent uses of multiculturalist rhetoric to shore up far-right white nationalist projects, see Daniel Martinez HoSang and Joseph E. Lowndes, Producers, Parasites, Patriots: Race and the New Right-wing Politics of Precarity (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2019).

[5] In September 2019, Lopez received a letter from the seminary informing him that his position would be eliminated at the end of the calendar year. For more on how his extreme anti-LGBT activism impacted his employment at this private Christian institution, see Collen Flaherty, “Anti-Gay and Unemployed,” Inside Higher Ed, Dec 11, 2019.

[6] Pushing back against reductive progressive narratives about a “crisis” in the economic structure of the four-year university (which obscure the historical inaccessibility of a liberal arts education for poor and lower-income students), Gillian Harkins and Erica R. Meiners point to “a transformation taking place in the values associated with higher education, including a decreasing public stake in humanistic or arts education and increasing investment in job readiness and science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) fields across two and four year educational attainment levels.” (“Beyond Crisis: College in Prison through the Abolition Undercommons,” Lateral 3 (Spring 2014).

[7] For more on the place of the university within a broader rightwing political strategy, see Ellen Messer-Davidow, “Manufacturing the Attack on Liberalized Higher Education,” Social Text 36 (1993): 40-80 or, more recently, Ralph Wilson and Isaac Kamola, Free Speech and Koch Money: Manufacturing a Campus Culture War (London: Pluto Press, 2021).

[8] Kim Phillips-Fein, “How the Right Learned to Loathe Higher Education,” The Chronicle of Higher Education, Jan 31, 2019.

[9] For more on the US university’s imbrication in racial capitalism and white settler supremacy, see Craig Steven Wilder’s Ebony and Ivy: Race, Slavery, and the Troubled History of America’s Universities (New York: Bloomsbury, 2013); la paperson, A Third University Is Possible (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2017); Leslie M. Harris, James T. Campbell, and Alfred L. Brophy, eds., Slavery and the University: Histories and Legacies (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2019); and Davarian L. Baldwin, In the Shadow of the Ivory Tower: How Universities Are Plundering Our Cities (New York: Bold Type Books, 2021).