Interview by Christine Hong

Christine Hong: Sung-hee, you were at the heart of the International Solidarity Committee, tirelessly calling attention to the plight of the people of Gangjeong and their resistance to the remilitarization of Jeju. You first raised the alarm in the context of the Global Network Against Weapons and Nuclear Power in Space and were instrumental to galvanizing a broad international movement against the naval base in Jeju. Could you speak about why you, as someone not native to Jeju, became involved in this struggle?

Choi Sung-hee: Initially I had no knowledge about Jeju Island, even about April Third. Around 2007, I learned that Hyun Ae-ja, a National Assembly representative then in Jeju, was conducting a hunger strike against the Jeju navy base plan. The story gripped my attention because at the time, I was very interested in missile defense, Korean division, and war and peace issues more generally. I did some research and I felt that it was my struggle.

CH: You’ve just touched on two key instances of foreign—specifically U.S.—power and South Korean state power seeking to crush dissent and resistance in Jeju. I think it’s safe to say that few people in the United States know anything about Jeju, even though U.S. militarism, from the Cold War to now, has long impacted the island—its people, their lifeways, their relations not just to each other but also to the land, ocean, and all forms of life. Can you give us a fuller sense of this devastating “hidden history” between the United States and Jeju, both past and present?

SC: People in the United States are perhaps familiar with the April Third uprising and massacre, whose official period started on March 1, 1947 and ended on September 21, 1954, after the Korean War. At the time, Korea had just been liberated from Japanese imperialism but was under the authority of the U.S. Army Military Government (USAMGIK). The U.S. Army Military Government dominated Korea, including Jeju, for a three-year period between 1945 to 1948. During that time, the U.S. Army Military Government ordered the killing of Jeju islanders, labeling Jeju a “Red Island,” a communist island, because the people resisted the U.S. policy of a separated Korea. The Jeju people wanted Korea to be independent. This is the background to the uprising of the Jeju people and their massacre by the U.S. military government and its puppet, the South Korean government.

However, even before the liberation from Japan, people in Jeju could see U.S. bombers flying over Jeju Island. It is very important to remember that Jeju is located in a very strategic spot for any imperial power in the Pacific. Jeju was the only foreign land that Japan heavily militarized in its final confrontation against the United States and its allies during Second World War. For this reason, the U.S. military flew bombers over Jeju Island in its late-war face-off against Japan. Many Jeju islanders still remember the noise of the U.S. bombers flying overhead. After April Third, even though Jeju was a refuge for orphans during the 1950-53 Korean War, the United States operationalized former Japanese bases including a radar base. After the Korean War, it still used Camp MacNab as a training ground and a resort facility. From 1958 to 1973, when the U.S. war in Vietnam came to a formal end, MacNab was used as a radar base for the U.S. 5th Air Force. The base was returned to Korea in 2005, as part of U.S. military realignment policy, but some people still recall the U.S. military’s presence. And now, even though there is officially no U.S. base in Jeju per se, the United States can use any South Korean military base and facility anytime it wants, thanks to the South Korean-U.S. Mutual Defense Treaty, which was signed right after the Korean War in 1953. My point is that even though there is no U.S. base in Jeju, Jeju is still considered part of the United States in terms of its Indo-Pacific strategy.

CH: To what degree do the people of Jeju hold the United States responsible for the violence of Sasam?

SC:For the past few decades, there has been a constant people’s movement, including the efforts of the Jeju Catholic bishop Kang U-il, to have the United States apologize for its killing of Jeju islanders during the April Third period. The people have continuously claimed that the United States is responsible for the killing. Two years ago, Bishop Kang even made a speech at the United Nations about U.S. responsibility [during the UN Symposium on Human Rights and Jeju 4.3]. Since there has been no U.S. apology thus far, this is an ongoing task.

CH: How did Sasam reverberate in the struggle of Gangjeong villagers’ struggle against the construction of the naval base, which, as you’ve just described, is so critical to post-Cold War U.S. geostrategic policy in the region?

SC: The essence of the struggle is the same. What I mean is that both April Third and the anti-navy base movement represent struggles against a foreign power and the central government dominating and controlling the island people, regardless of the islanders’ will.

Let me offer a story about how the character of oppression during April Third massacre persists in the struggle in Gangjeong. Around 2012 or 2013 when the struggle was at its peak, right-wing protestors who were very pro-Jeju navy base came to the village. In response, the people of Gangjeong got very angry. One of the villagers who fought against these right-wing protestors was former Mayor Kang Dong-kyun. When he told them not to dare set foot in Gangjeong, they called him a “Red.” Mayor Kang was really annoyed because he had already been victimized by such distorted ideology. During the April Third period, people were killed on the basis of the false claim that they were communists. This anticommunist ideology justified mass death. In the Gangjeong struggle, the rightwing protestors called villagers who were just trying to save their village “communists.” I was shocked to witness the whole scene unfold because one of Mayor Kang’s relatives was killed during the April Third period based on the false assertion that he was a communist. Now, he was the one who was being red-baited. In this story, you can see how April Third continues in the Gangjeong struggle.

I also remember when many policemen from the Korean mainland came to the island to suppress the protestors—the villagers and the activists—especially during the Gureombi Rock blast period in 2012. This, too, was a pattern of repression familiar from the tactics deployed against the islanders during the April Third period.

CH: I remember the deployment of mainland police, too. What you’ve just shared reminds me of another terrible story. During the Gangjeong farmer Jeong Young-hee’s speaking tour in the United States in 2013, we organized with the Center for Korean Studies at UCLA for her to present on the anti-base struggle as part of an “Ending the Korean War” conference. Under the neoconservative Park Geun-hye administration, the Korean consulate closely monitored all Korean studies events in the United States for their political content. If you can believe it, someone from the consulate advised the center at UCLA that Jeong Young-hee was a terrorist.

SC: I heard that story from Jeong Young Hee. It’s crazy that Jeong Young-hee and others—who are farmers—were called terrorists. That’s how the dominating class has oppressed people who resist in their fight for democracy not only in Gangjeong but anywhere. In Korea, the division of the peninsula is utilized to oppress people.

CH: What you’re saying about the opportunistic mobilization of the division of Korea reminds me of what Kang Jeong-koo of SPARK (Solidarity for Peace and Reunification of Korea) has said about how the divided Korean peninsula, as a permanent crisis zone, presents a flexible opportunity to enact power transitions. It can delay or advance, playing into an imperial politics. Korea’s ongoing division, which in the first instance the people of Jeju protested against, tragically persists to this day and fuels the targeting and persecution of anti-base protestors.

Can you update us on the Gangjeong situation, now that the naval base is a fait accompli? At the start of this year, the Save Jeju Now website featured solidarity statements from the international community, marking 5000 days of struggle against the base. In what forms does the resistance continue?

SC: As of January 23, the Gangjeong struggle hit the 5000-day mark. What has happened to Gangjeong is more than this number can capture, of course. The base was completed in 2016. About five years have passed since then. If you come to Gangjeong again, you can see how the landscape has changed. First of all, you will see the Jeju naval base instead of the beautiful Gureombi rock [a volcanic coastal rock formation and sacred site in Gangjeong]. You can see how the tangerine trees have been replaced by 3-4-story high buildings. You can see how the military road is being constructed, destroying the Gangjeong stream. Recently, in their efforts to halt the military road construction in order to preserve the stream, people filed a lawsuit against the South Korean navy and the Jeju Island government. Time will tell if this is successful. Militarization has come with development—overdevelopment. In Gangjeong today, you can see how the military comes hand in hand with capitalism, tempting the villagers with the message that “With this military base, you can have economic development.”

This is very sad. We can see that many villagers are not active anymore in the anti-base struggle. Many just look sad. Even though they are very sad in their deepest heart about the loss of Gureombi rock, many villagers seem to have lost their courage to rise up so the struggle is mainly carried on by the activists nowadays. The remarkable thing is that most of the activists have stayed in the village, and I am one of them. Of course, many activists have left but newcomers have also arrived because people feel that this struggle is very important not just for the village but for the peace of Northeast Asia. We activists agree that we must continue the struggle.

The struggle still has a daily structure: at 7 a.m., one hundred bows; at 11 a.m., the street mass often led by Father Mun Jeong-hyeon and Father Kim Sung-hwan; at noon, the human chain. If you meet the peace activists here, you can see how their interests and talents are diverse and creative. Even though the activists may seem somewhat isolated from the village, the peace movement persists, and the movement is very diverse. There are many activists who are very interested in peace education; they have developed a peace education program and made efforts to be teachers themselves. Some are interested in and very committed to monitoring the construction of the military road. And some are committed to kayak protest, which is wonderful. Those are only a few examples. It is through such actions that we can continuously transmit what we observe to the world and organize actions, if necessary.

In my deepest heart, I still believe in the villagers. They are sadder than us. Sometimes I think they will rise up again. I have faith in them. And we must ask the question: Even though they are no longer active, have the villagers truly given up the struggle? I am not so sure. Let me give you an example. There is a native villager, Kim Jong-hwan, who for the last ten years has been very committed to managing a protest community restaurant and providing daily meals to the activists. I really think the reason that we could continue this struggle is thanks to the meals he prepared for us. Last year, we learned that he was diagnosed with cancer. He had to have a major operation. I have come to believe that illness, though not intended, should be understood as a form of resistance. He is one of the villagers who greatly misses Gureombi as it once was.

I also remember a male villager who is similar in age to me. He is a sort of macho guy. But I saw his tears the day before the blasting of Gureombi rock began. He said to me, “Do you get it? Gangjeong is Gureombi. And Gureombi is Gangjeong.” This clarified to me that Gureombi was the heart of the village. The military stabbed the heart of the village by destroying Gureombi to build the base. And if you are native to the village, how can you continue living? Enduring, just to continue to live in the village, requires tremendous courage. If someone only looks at us, the activists, they might be overlooking the villagers who have endured for a long time and sacrificed many things during their hard struggle against the base.

CH: Is there tension between the activists and villagers today?

SC: I would say, “Yes.” What I have found is that after the completion of the Jeju navy base, the villagers are not active anymore. And you can imagine the gap between the villagers and the activists. I can understand how it would be uncomfortable for the villagers to see activists continuously fighting because the activists are a living reminder that they lost their home town. What I want to emphasize is that militarization divides people—between pro and con villagers, but also between villagers and activists. This division is very systematic. One should understand that this is how militarization works. In order to fight against militarization, we must understand the nature of the system. Having this understanding means that we will seldom lose faith in the people who have been, are, and will one day be with us.

But I should not be naïve either. The current Gangjeong village association is very concessionary to the South Korean navy. Last August, the association jointly signed a so-called civilian-military co-prosperity and development agreement with the navy. This means the village has now become a colony. Before that, two years ago, the village association took measures to disqualify activists as “residents” by retrogressively revising its village code so that activists can no longer express their opinions in village meetings. This process has been very systematic.

President Moon Jae-in is also very responsible for further militarizing Gangjeong. He was the one behind this civilian-military agreement. In 2018, when a majority of the villagers, including the current village association members, initially voted against the international fleet review, President Moon sent his secretaries to Gangjeong to persuade the village association to accept the fleet review on the condition that President Moon apologize for the government’s violent drive to construct the Jeju navy base. Of course, this was a very deceptive proposal. Despite the criticism of anti-base villagers, the village association held a meeting to vote on this proposal. By the second vote, a majority of villagers agreed to accept the fleet review, which was carried out on the Jeju navy base and the sea around Gangjeong in October of that same year.

During the fleet review, President Moon paid a visit to Jeju and, during his speech, stated that he would make the Jeju navy base a “stronghold for peace.” It is horrible how his choice of words echoed Ronald Reagan’s 1980s’ slogan, “Peace through power.” It is very clear that the Moon government is ready to further militarize Jeju, which means that Jeju could be increasingly incorporated into the U.S. Indo-Pacific strategy. It is also striking how the word, “peace,” has been contaminated in application to Jeju, which was called Peace Island following former South Korean president Noh Moo-hyun’s 2003 apology for the government’s responsibility for the April Third massacre. Recently, President Moon used the term, “civilian-military integration,” when he made a speech on the opening of South Korea’s “Space era.” I was horrified because this phrase sounds like the advent of fascism. I wonder whether this phenomenon is particular to here or whether this same problem exists everywhere in the world now.

Given the enormous stakes, the activists’ task to connect with the villagers may not be easy but, yes, it is a task which should not be ignored.

CH: You’ve described how the villagers have adjusted to the injustice of the base. I know this is a delicate subject, given the history of how the South Korean government, under Lee Myung-bak, promised the haenyo (sea-diving women) financial support, a retirement home, and education for their children in return for their support of the base. Insofar as the U.S.-driven geostrategic imposition of the base on Gangjeong has violently torn apart the fabric of social relations and daily life in the village while destroying the land and waters, I’m wondering where do the haenyo dive, now that their waters have been put to military use?

SC: As you know, the sea-diving women in Gangjeong, many of whom are old and uneducated, were tempted by the navy in the beginning. Now, they clearly know that they have not benefitted from the Jeju navy base because now that it has been constructed, you can no longer catch sea urchins or big fish near Gangjeong. If you want to catch big fish, you have to go far out to sea. All the sea resources have been destroyed around the Jeju navy base. Some UNESCO-designated soft corals remain but many have disappeared. Now the sea-diving women realize what really has befallen them.

CH: Could you speak more broadly about the remilitarization of Jeju and the dangers of the present? The naval base was constructed supposedly to ward off a North Korean missile threat but, as we know, it was really directed against China. The use of North Korea as a bogeyman to encircle China was a signature feature of Obama’s “pivot” policy to Asia and the Pacific. We now have a new U.S. president, Joseph Biden, who, as a firstmost priority, dispatched his secretary of state, much as Obama did, to Asia to fortify the possibility of a trilateral alliance between Korea, Japan, and the United States.

SC: First of all, the Indo-Pacific is important for the United States. It occupies more than fifty percent of the earth. A year ago, former U.S. Defense Secretary Mark Esper stated that by 2045, the United States aimed to have about 500 U.S. military ships in the Pacific, about six of which would be light aircraft carriers. All of this boils down to the fact that the United States is really focusing on Indo-Pacific strategy, with an eye to global dominance. If you look at a map, Jeju is strategically located just in front of China. Here, I want to emphasize that it doesn’t matter whether a base is an official U.S. military base or not because the U.S. military can use alliance bases anytime it wants. So the peace movement should not make any mistakes on this point. We should say, “No base,” not “No U.S. base.”

One must also understand that if there is a Jeju navy base, there must be an air force base. Around 2015, the central government in Seoul announced that it was planning to build a second airport in Seongsan in the eastern region of Jeju. There was no overt mention of the airport being an air force base, but by assessing the situation, people clearly realized what its purpose would be. In a recent public poll, people expressed their opposition to the second airport base project, but the Jeju governor, who is very much in favor of the second airport, twisted the poll’s results. He has been a driving force behind the second airport, but the central government hasn’t made its final decision yet so this issue is ongoing.

One thing I want to point out is that Gangjeong activists are now everywhere in Jeju Island. They are not only fighting for Gangjeong; they are fighting the remilitarization of Jeju, including the “No Second Airport” struggle. Very recently, we became aware of another issue: plans to establish a National Satellite Integrated Operation Center in northeastern Jeju. There is no overt mention of the military in this case either. However, from my research, it is very clear that the center is related to military matters and would be incorporated into U.S. Indo-Pacific strategy. We can see that the technique of militarists is not to mention the military when converting sites to military purposes. Instead, they deceptively claim they intend to build a civilian facility.

CH: You, alongside many Gangjeong residents and committed activists from the mainland, were imprisoned for obstructing the “business” of base construction. When we first met almost a decade ago, you were in prison with a thick plastic partition separating us and a guard standing behind you. Can you address how corporate capital has driven the remilitarization of Jeju?

SC: Insofar as the military base increases their profits, we can see corporate capital and the military cooperating together. The military knows that if it declares it wants to build a military base in your village, nobody would support that so it has to provide some carrots. That’s how Samsung, Daelim, Posco, and many big corporations in South Korea involved in the construction of the Jeju navy base proceeded, as I alluded to earlier. In the case of the Jeju navy base, it is very interesting to know that the base has another name, the Jeju “Beautiful Tourism Complex Port for Mixed Civilian-Military Use.” So you can see how they connect militarism to tourism to lull people into thinking that this is not just military base but a beautiful tourist port like Sydney and Pearl Harbor, which are the favorite examples raised by the South Korean government.

CH: When I was in Gangjeong in 2011, I saw utopian tourist propaganda of the then-future base on giant boards lining the streets. These images were reflective of a distorted worldview, showing people skating and white visitors leisurely strolling while eating ice cream. It reminded me of Louis Owen’s concept of militourism and Teresia Teaiwa’s celebrated account of the bikini swimsuit as a displacement of the horror of the nuclear testing at Bikini Atoll.

SC: In the Navy’s advertisement board for the mixed civilian-military complex, all the women are wearing miniskirts. This is one way that capital is mobilized for militarization. In the case of the Gangjeong struggle, we can also see how the judiciary, as part of the system, cooperated with the military and capital by giving sentences that included the imposition of heavy fines on the protestors. Some of the protestors were even the targets of civil lawsuits pursued by the construction companies.

CH: Can you say more about how criminalization and related to this, incarceration has served as a method, by the South Korean government as a subimperial power, of quashing anti-base resistance?

SC: Through criminal punishment and civil punishment, corporate capital has sought to stifle the protestors. But accompanying this is also ideological oppression. When the protest was at its peak, the right-wing media began labeling the anti-base protestors “communists” and “outside powers.” In effect, the message has been “You are not native to the village. Why are you intervening? You are not qualified to resist.” We have to recognize this as the government’s ideological method for disqualifying us from taking part in this struggle. We should fight against this kind of ideology. So, our response is “What are you saying? This is a national policy and we are citizens. This base is paid for by our taxes. This is our job.”

Moreover, many internationals came to Gangjeong, including you, to express solidarity. The presence of internationals was amazing because it showed us, villagers and activists alike, that this base is not simply a local struggle. Resistance to this base is an international struggle. Internationals came here because they also thought opposing the base is their job insofar as it relates to peace in Northeast Asia. For example, there was a UK activist named Angie Zelter who was arrested three times. I was the translator between the police and her. When the police asked her, “What’s your name?” and “Where did you come from?” Angie Zelter replied: “I came from Gureombi rock.” She did not disclose her nationality. Her gift to us, when she left, was a flag of the earth. The meaning was very clear. This is a very important story.

I should also add that many internationals have been oppressed by the South Korean government because of their solidarity with the Gangjeong struggle. Beside Angie Zelter who was forced to leave as a result of an exit order, there was one French citizen, Benjamin Monnet, who was slapped with an injunction, twelve internationals who were arrested, and twenty-three internationals who were denied entry. Many internationals, even though ban has been lifted for most of them now, were traumatized by these horrible experiences. Whenever I think of them, I am really so sorry for them. This is further evidence that this struggle is international and that the South Korean government is afraid of internationals. In the global anti-base struggle, the government, whether South Korean or Japanese, has tried to define the qualifications of the fighters. We must resist that.

I also want to express my gratitude to all the internationals who came to the village and supported and encouraged us with their love and friendship. You are surely one of them. I wish to express special thanks, among all the activists, to Bruce Gagnon and the Global Network against Weapons and Nuclear Power in Space. He and the Global Network have really encouraged our struggle. They helped us to spread the news of struggle so that more and more internationals came to the village.

CH: What the incarceration of so many villagers and activists clearly demonstrates is the political nature of policing relative to the anti-base struggle in Jeju. I have learned so much from this conversation about the importance of the temporality of anti-base activism. Our timeframe must necessarily span generations. Even as we honor those who were indiscriminately killed in Sasam, we also realize that what the people of Jeju called for in those early Cold War years—Korea’s independence and self-determination—is far from realized, and so the struggle continues.As we begin closing our conversation, I want to ask you, as an artist—as is your partner, the Jeju native Goh Gil-chun—about the extraordinary blooming of art and cultural expression that characterized the anti-base struggle in Jeju. Can you speak about this?

SC: What I’ve found is that many people who come to Gangjeong become artists. Many young activists—and me, too—usually do not have any ties to any one civic group. If you compare us to other civic groups in Korea, ours is a relatively free and creative group. We mostly just came to Gangjeong as individuals. Our networks are thus very free, and we do not like strict rules. In such a setting, creativity flows. Everyone encourages one another to undertake art projects. And of course, most importantly, the nature of Gureombi rock and Gangjeong stream gives us a lot of inspiration.

CH: What actions can the international community take in solidarity now?

SC: Jeju is important for the peace of Northeast Asia, but I also want to remind people that Jeju is one of many islands that are militarized by the United States as part of its Indo-Pacific military strategy. If you are concerned about Jeju, you should consider the plight of other islands, too. One of the things we must do to galvanize international solidarity is to connect our struggles together. Curry, a member of the international team, is an American who has been living in Gangjeong for more than five years. She is now organizing, along with the St. Francis Peace Center, an event about resistance to the militarization of islands, which starts on April 10.

We must also end the Korean War. The Korean War has never officially ended, and this irresolution has become a pretext for military build-up in the Pacific. Ending the Korean War is one of the core tasks to establish peace in the Pacific and the world.

Update: On March 7, 2020, on the eighth anniversary of the dynamiting of Gureombi rock, Dr.Song Kang-ho and his colleague Ryu Bok-hee entered the Jeju navy base and, seeing the small remnant of Gureombi, prayed for peace. In the first court decision, Song was sentenced to two years’ imprisonment. Ryu was similarly sentenced to two years’ imprisonment but with three years probation. As of March 31, 2021, the Jeju local higher court upheld the lower court’s decision, meaning that Song, who has been imprisoned for more than a year, will remain behind bars for another year. Their struggle demonstrates that April Third continues in Gangjeong. Even though the government committed crimes in its undemocratic imposition of the base, which serves U.S. Indo-Pacific strategy, those responsible for building the base have never been punished while the people who protest against militarism are routinely excessively punished. Although seventy-four years have passed since April Third, the uprising’s essence, in the face of oppressive foreign and state power, persists in the people’s resistance to the militarization of Gangjeong and Jeju.

AUTHOR BIOS

CHOI Sung-hee was born in the mainland of Korea but moved to Gangjeong village, Jeju, in 2010, to join the struggle opposing the building of the Jeju navy base. The base was completed in 2016 but she continues to oppose the base and claims the base should be shut down for the true demilitarization of Jeju, the Peace Island. She also joins other struggles such as “No to the Jeju Second Airport (which is suspected to be an air force base)” and “No to the National Satellite Integrated Operation Center” currently planned in Jeju. She has worked in the village international team which has published the English language newsletter titled Gangjeong Village Story, since 2011. She also works for the Gangjeong Peace Network, Association of Gangjeong Villagers Against the Jeju Navy Base, People Making Jeju a Demilitarized Peace Island, and Inter-Island Solidarity for Peace. She is also a Korean board member of Global Network against Weapons and Nuclear Power in Space. See savejejunow.org

Christine HONG is Associate Professor of Literature, director of Critical Race and Ethnic Studies, and co-director of the new Center for Racial Justice at UC Santa Cruz. She is the author of A Violent Peace: Race, Militarism, and Cultures of Democratization in Cold War Asia and the Pacific. Along with Deann Borshay Liem, she co-directed the Legacies of the Korean War oral history project. She serves on the board of directors of the Korea Policy Institute, an independent research and educational institute, and she is the co-editor of the journal of Critical Ethnic Studies.

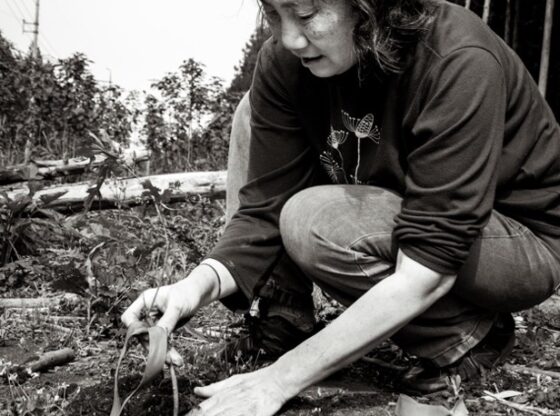

Choi Sung-hee in the Bijarim-ro forest, 2020. If the second airport, which people suspect to be an air force base, is built in eastern Jeju, this forest will be greatly destroyed as the adjacent road, which would lead to the airport, will be expanded. Photo by Oh Young-chul.

Choi Sung-hee in the Bijarim-ro forest, 2020. If the second airport, which people suspect to be an air force base, is built in eastern Jeju, this forest will be greatly destroyed as the adjacent road, which would lead to the airport, will be expanded. Photo by Oh Young-chul.