By Rayhan Jhanji

The Classroom Building (hereafter referred to by its former name, the Carr Building) has become a centerpoint of the struggle for activist students against Duke’s Board of Trustees, a traditionally patriarchal and white cabal which resists change from all sides. It is my opinion that the renaming of the Carr Building was necessary and just. Yet, with the renaming process almost complete, I worry that we will lose sight of the reason that the movement to rename Carr Building was so needed–because Julian Carr’s sentiments of racism and white supremacy exist today in a variety of forms. Although renaming the Carr building is a step in the right direction, it does not free us from conversations that need to take place about the steps society needs to take to dismantle structural racism and inequality in America. To do so, I propose that Duke University put up a counter-monument within the Classroom Building in a place that is prominent yet does not force its reminder on individuals that are triggered by the bigotry and white supremacy of Julian Carr. Perhaps the counter-monument could be in the form of an empty space in the Classroom building, or perhaps it could take the form of an exhibit of all Julian Carr’s actions, including the good and bad. Regardless, this counter monument should remind students, faculty, and alumni of the complicated past that our institution has had between fostering diversity among its student body and supporting bigotry throughout the Jim Crow era.

Prior to the effort to rename the Carr building, only a small percentage of Duke students knew about the complicated legacy of the individual for which the building was named. When I first came across the name of Julian Carr, I was researching the architectural history of Duke University and the Durham/Chapel Hill area and found a speech that Carr gave at the dedication of the Silent Sam statue in 1913. I felt nauseated at the bigoted language Carr used to describe people of color. In the midst of a speech that extolls the sacrifices and nobility of the Confederate soldier while tactfully ignoring the slavery the Confederacy fought for, Julian Carr tells a personal anecdote, as Jacob Remes cited in his essay, that describes his encounter with a black woman. There is no defending the bigotry displayed by Julian Carr in this speech, no putting it into context, no justifying it based on the norms of the era—we must not support and perpetuate any individual who is willing to make such comments.

In my research as an undergraduate fellow for the Humanities Unbounded MicroWorlds Lab, I have had the opportunity to study monuments, public memory, and the different methods that societies have used throughout the ages to commemorate and remember. It is my belief that a counter-monument would provide an appropriate solution to the problem of the Carr Building, as it will simultaneously force us to reconcile and recognize our checkered past. Counter monuments are monuments that reject traditional monumentalist theory of imposing structures and embraces a reflection of history that fits into the landscape.

Only through continuous and active discussion of the checkered legacy of Julian Carr can we continue to build a future in which the bigoted attitudes espoused by the likes of Carr will cease to exist. During the 1990s, when Germany was deciding how to memorialize the Holocaust,noted artist Horst Hoheisel presented the radical idea to raze Brandenburger Tor, a symbol of Prussian might, to the ground and leave the void to symbolize the loss of Jewish life at the hands of Nazi Germany. Even though this proposal was not implemented, it nevertheless forced the conversation about Nazism and the role of remembrance. James Young praises attempts to continue such conversations, asserting “that the surest engagement with Holocaust memory in Germany may actually lie in its perpetual irresolution, that only an unfinished memorial process can guarantee the life of memory.” This is by no means an attempt to conflate the Holocaust with American racism but it is an example of the counter memorial as an effective tool for remembrance.

As a student of color at Duke, I am less bothered by the name “Carr” itself, but rather what it represents–a legacy of white privilege and supremacy that is embodied by our Board of Trustees. Once discussions about renaming the Carr Building were underway, it became clear that the Board and President Price were resistant to change for fear of losing donor support. It was precisely at this point that I become personally uncomfortable sitting in the Carr Building, where, as a History Major, I regularly attend classes and conduct research. Julian Carr is dead. For me, he is inconsequential at this point in time. However, the members of the Duke Board of Trustees are alive and hold the power to change names throughout East and West Campus. It was the Board’s resistance to change that really bothered me with name “Carr” acting as a placeholder. Despite my disdain for the stagnation of the Board of Trustees, I cannot blame them solely for their inaction. The blame lies on all of us. Every single member of the Duke community is responsible for actively pushing to reform our campus to make it more inclusive.

The renaming of the Carr Building is not about forgetting an influential founder of our esteemed university. In fact, it should be about remembering his legacy. We should never forget Julian Carr, for BOTH his good deeds in helping found Duke University and his horrendous and malignant attitude towards individuals of color. This is why the renaming of the Carr building is so important. It is our job as historians to constantly criticize and reshape our own histories and legacies, so that we refrain from celebrating white supremacy and bigotry. For Duke students, our biggest task is to spearhead discussion and change, as we represent the largest and most vocal group within the university. Whether it is through the construction of a counter memorial of empty space, the creation of a permanent exhibit within the Classroom Building, or any other tool of remembrance that we choose, I believe that our priority should be continuing the dialogue around the Carr building. Discussing Julian Carr is a stepping stone from which we can discuss the social and structural disparities that people of color continue to face today.

AUTHOR BIO

Rayhan Jhanji is a sophomore at Duke University pursuing a major in History. Rayhan has a deep love for archival research, which led him to join the Wired! Lab at Duke as a part of the “Building Duke” project. In the Wired! Lab, Rayhan’s research focuses on the historical narrative of the physical space that Duke inhabits and how the transformation of that space influences the identity of Duke University. Rayhan is also an undergraduate fellow in the MicroWorlds Lab, where his research incorporates public memory and monuments. Rayhan hopes to teach History one day, with the goal of inspiring a new generation of historical researchers to pursue what they love.

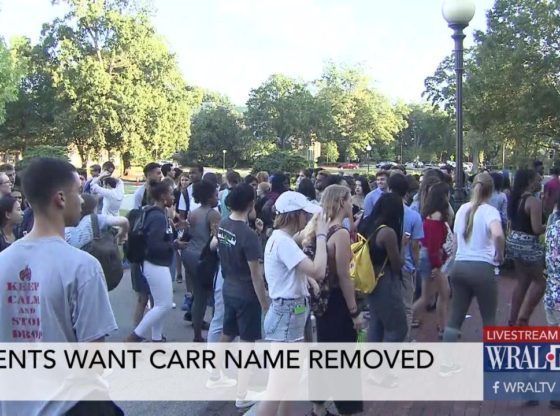

Duke Students Want Carr Name Removed, September 5 2018. via WRAL.com.

Duke Students Want Carr Name Removed, September 5 2018. via WRAL.com.